Like digital IDs, mobile driver’s licenses (mDLs) aim to elevate identity verification to a new level, where documents are pre-built for machine-to-machine verification, and a verifier can request only specific data elements. And there’s a lot more.

Like with digital IDs, mDL implementation has been uneven across countries as 2026 begins. The main reason is that setting up a working mDL ecosystem requires a lot of effort: not only an issuer app, but also reader implementations that follow the protocol, trust distribution that keeps issuer keys current, and acceptance rules that relying parties can apply consistently.

In this article, we will take a closer look at how mobile driver’s licenses appear in the world right now, and how mDL verification works in principle.

Subscribe to receive a bi-weekly blog digest from Regula

What is a mobile driver’s license (mDL)?

An mDL is a government-issued driving credential stored on a phone in a standardized, signed data format.

During driver’s license verification, the holder’s device shares specific attributes through a session with a reader. The reader validates what it received, then produces a result that an operator or backend system can rely on.

Key actors in an mDL ecosystem

There are usually four distinct roles to highlight in mDL implementations:

Issuer: The authority that creates the credential and signs the data (in the US, typically a state Department of Motor Vehicles).

Holder: The person whose credential lives in an issuer app or a device wallet.

Verifier (relying party): The organization requesting data and making a decision.

Reader: The verifier’s software and hardware that runs the protocol and validation logic.

Note: In practice, a “reader” is rarely a single screen. It typically includes a trust store (issuer certificates and trust anchors), request presets that control what gets asked, and result handling that controls what gets displayed and what gets stored.

What data is shared

A mobile driver’s license can carry a rich set of identity and credential elements, but the reader only receives the specific elements it requests and the holder approves, plus the cryptographic material needed to validate them.

Typical attributes shared include (but are not limited to):

Identity attributes: Name (given name, family name), date of birth, place of birth (sometimes), address elements (when needed and available), issuing jurisdiction and credential identifiers (to tie the record to an issuer and to support audit trails).

Credential details: License class/category, restrictions and endorsements, issue and expiry dates.

Portrait and images: The holder’s portrait image, used for a post-match comparison by an operator or an on-device check.

In practice, age checks for restricted purchases are one of the most common use cases of mDLs (at least, in the US). Many mDL reader implementations support age checks that can return an explicit “over/under” threshold result without revealing the owner’s exact date of birth or home address.

A word on presentation methods and standards

Most people encounter mobile driver’s licenses in a face-to-face setting — a traffic stop, for example. This is referred to as proximity presentation: the holder and the reader are physically near each other, they start a session using QR or NFC, and the credential is shared inside that session.

Then, there’s online presentation, where a website or an app asks for mDL data over the Internet. The credential format can stay the same, and the idea of selective disclosure stays the same, but it is the environment that changes. The request can now be delivered through a link, a QR code on a screen, or a browser-mediated flow.

It’s important to note that these two presentation methods are regulated differently. For example, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has put forward two separate reference points:

ISO/IEC 18013-5 for proximity presentation.

ISO/IEC TS 18013-7:2025 for online presentation.

Different presentation methods face different kinds of threats, so these standards were separately developed to adapt to them.

Proximity presentation assumes co-presence, which almost eliminates remote attacks, but it does not remove the need for strict reader behavior. The practical risks tend to be “local”: accepting a screenshot or a recorded animation, skipping post-match comparison, or running a reader with outdated trust material.

Online presentation moves the same credentials into a remote workflow, adding more attack surface. Session forwarding (where an attacker initiates a transaction and persuades a holder to complete it for them) and relying-party impersonation are the two most common potential threats.

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on proximity presentation cases as these are by far the most common.

United States’ mDLs as the most robust live ecosystem (plus other countries’ cases)

The US has by far the highest concentration of active issuers and high-frequency relying parties. In turn, that brings fast iteration: acceptance sites encounter failure, reader vendors fix them, and issuers adjust policies and comms — all in short periods of time.

How many US states have mobile driver’s licenses?

This question doesn’t have a straightforward answer. First, this number is growing almost every month.

Second, states can run multiple mobile credential products, with some being tied to ISO mdoc standards, and some not. This is an important distinction as an ISO mdoc is a signed digital document format, strictly defined in the aforementioned ISO/IEC 18013 (more on that later).

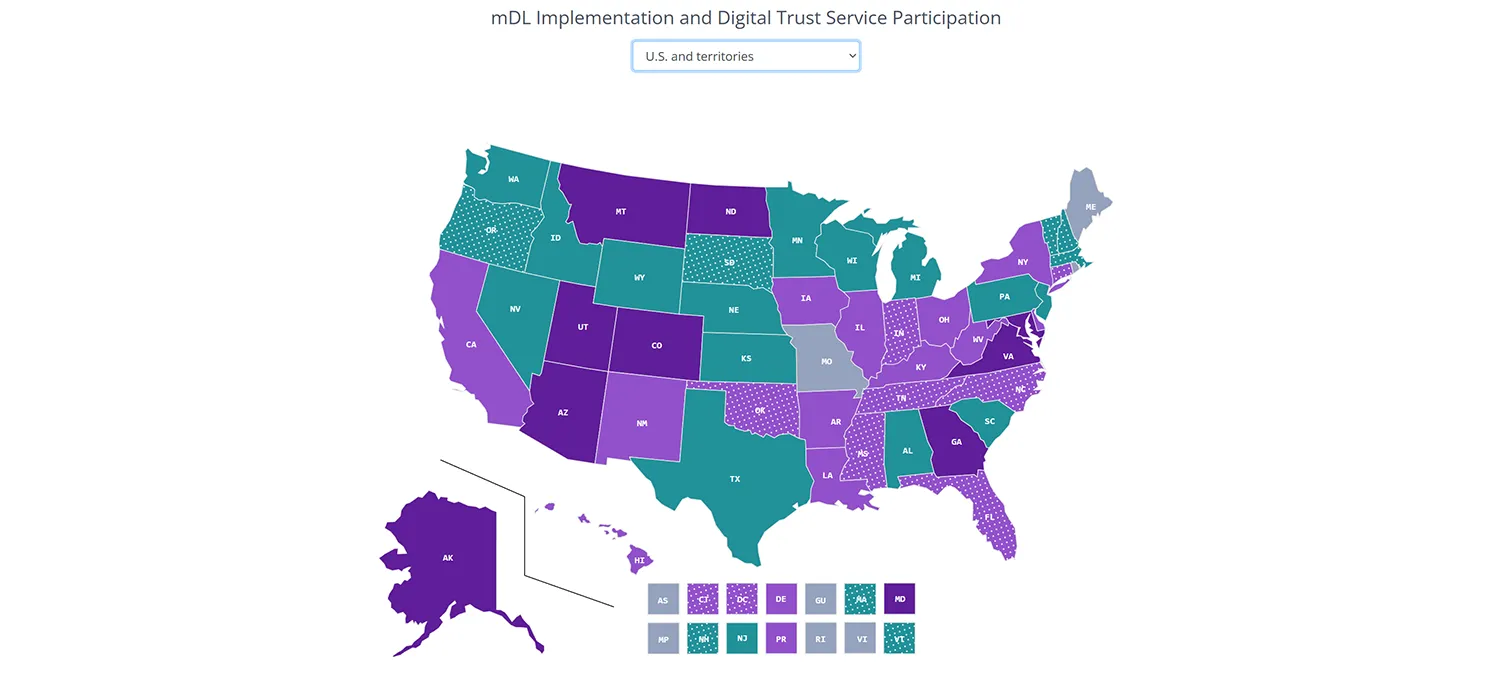

As of mid-January 2026, the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA), lists 21 US states plus Puerto Rico: Alaska, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia.

However, this count is specifically based on credentials Transportation Security Administration (TSA) accepts for checkpoint use. It does not cover every pilot or every limited venue acceptance.

The AAMVA map shows all U.S. states with active mDL programs in solid dark/light purple. Implementations in progress are shown in dotted light purple.

As for specific adoption numbers, some states have reported the following data:

Are there different kinds of mobile driver’s licenses in the US?

The issuance of mobile driver’s licenses in the US is best described as multi-channel: many states issue through a state app, device wallets, or both.

Utah's mobile driver license uses a standalone app, while Arizona's gets integrated into a Google/Apple wallet. Sources: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.getgroupna.mdl.app.utah&hl=en and https://azdot.gov/google-wallet.

Even more duality can be found when you dig into the details: mDLs can appear in two types. Whether it’s a police officer or a counter clerk, both will look like a license on a phone and have the same user experience, but verification stacks will treat them as separate products with different reader flows:

Standards-based mDL (ISO mdoc style presentation): This is the model the AAMVA anchors on: an mdoc is a mobile credential presented through a defined protocol to a reader, with selective disclosure and cryptographic validation. The AAMVA explicitly frames mDLs through ISO/IEC 18013-5 (proximity) and positions its trust services around issuer authentication and interoperability.

Phone-based “Digital ID” programs that are not necessarily an ISO mdoc:

Some state solutions focus on visual presentation plus a scannable code (often a QR) that a verifier app can validate. Colorado’s myColorado verification model is one example.

This begs the question: are non-ISO “mobile licenses” less reliable? Not necessarily.

An ISO mdoc is designed so a reader can run a standardized protocol and get a result that is backed by cryptography, while a non-ISO doc relies on:

A visual card view with animated/hologram effects.

A QR/barcode that a verifier scans and then checks against a backend.

A server-refreshed token (the app calls home and updates a timestamp/graphic).

A domestic-only proprietary format that works only with one verifier app or one country’s infrastructure.

In practice, it does make non-ISO docs insecure, but they usually provide weaker or less standardized verification guarantees, and they are much harder to scale across different readers, issuers, and cross-border use cases.

Developments outside the US

Outside the US, the most interesting programs also tend to fall into two same categories:

Places already running ISO-style mdoc verification, even if only for a narrow use case.

Places with “official digital license” adoption at national scale, where the verification story is strong domestically but not yet an ISO mDL ecosystem.

Below we have assembled three of the most interesting non-US examples.

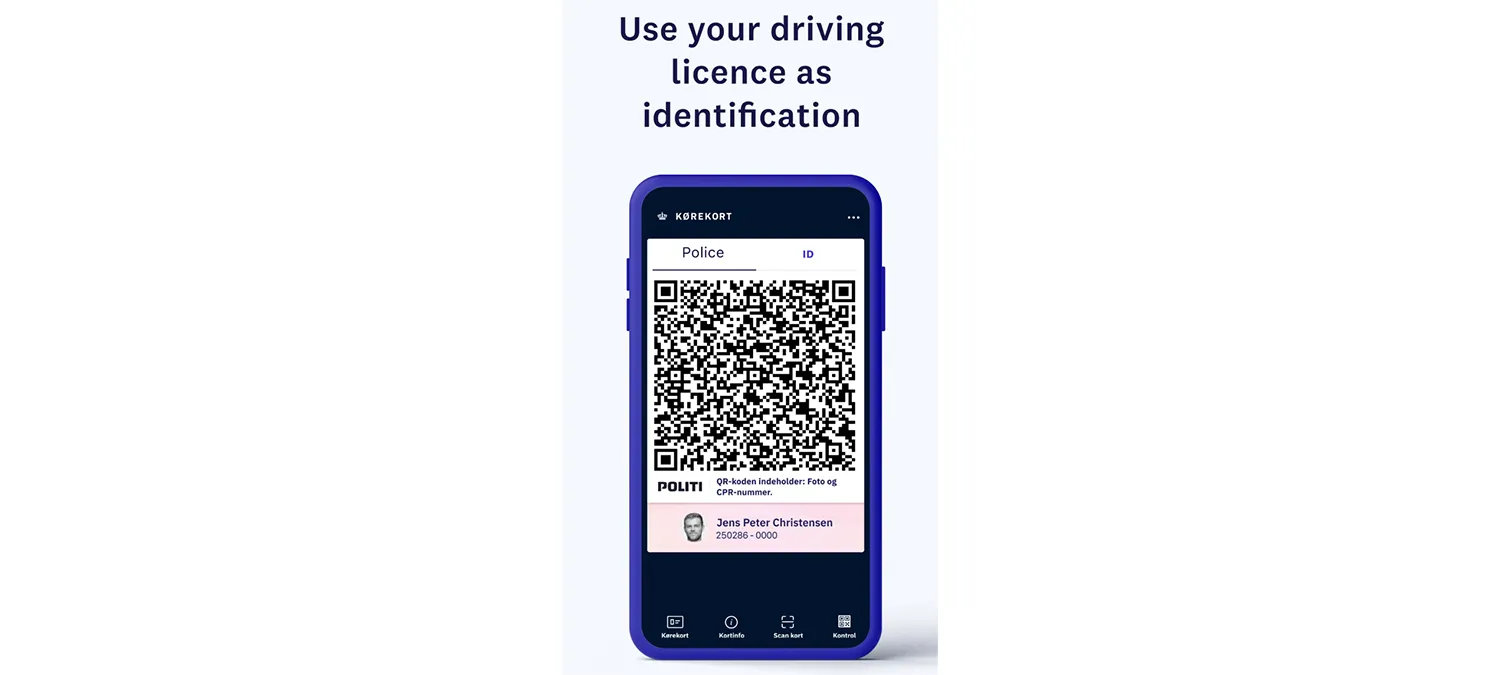

Denmark’s early mass adoption

Denmark is one of the best examples of national-scale adoption of a mobile driving licence app (with some caveats). The launch took place back in 2020, and, as of late 2025, 2.1 million citizens have created their digital driver’s license in the app.

Source: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=dk.digst.mdl&hl=en

The official Kørekort app listing states that it’s a voluntary supplement to the physical license and that it functions as a valid driving licence in Denmark, letting users leave their plastic card at home as long as they can show the app. But, in a technical sense, Denmark’s case isn’t ISO mdoc-based (just like some US states).

As such, it has made a good case for non-ISO docs. Denmark first focused on rolling out a product with good user experience and high potential for everyday use, rather than interoperable mDL verification — and has found success.

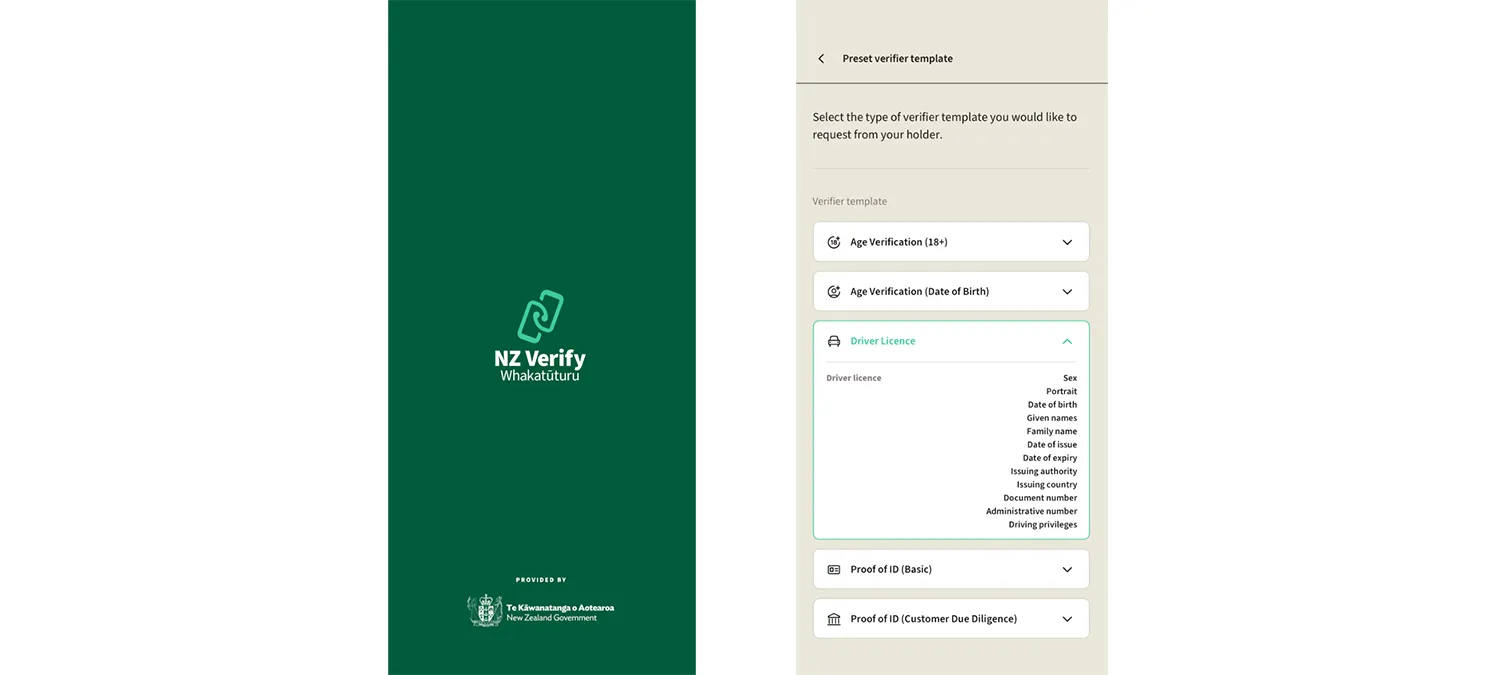

New Zealand’s verification without issuance

New Zealand is another interesting case as they don’t have a domestic mDL issuance program of their own, yet they boast a verifier app built to accept international ISO mdoc-based mDLs in everyday tourism workflows.

Source: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=nz.govt.nzverify&hl=en

The Department of Internal Affairs describes NZ Verify (also referred to as Whakatūturu) as a way for businesses like car rentals and hotels to verify select international mobile driver’s licenses using only a phone. It explicitly lists Queensland (Australia) plus a set of US state issuers (and Puerto Rico) that the app can verify.

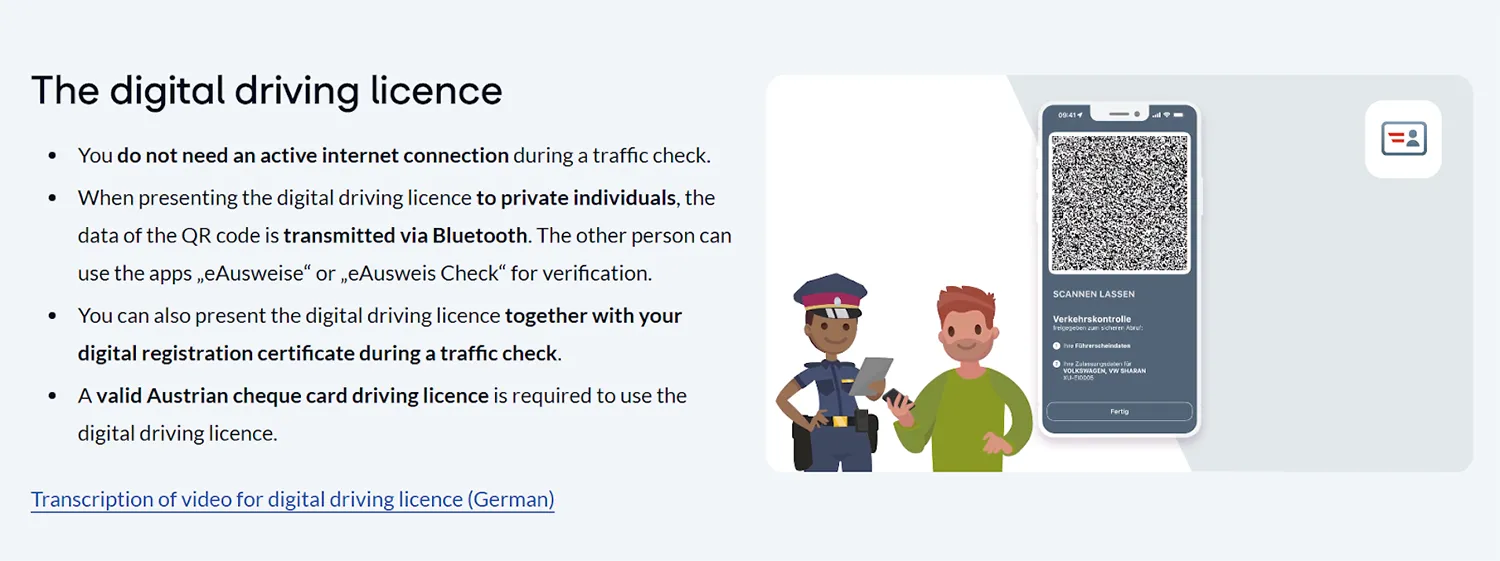

Austria’s peculiar hybrid

Austria’s case involves both ISO and non-ISO docs within one system, making it rather unique.

The holder uses the government eAusweise app, and access is tied to ID Austria (the national eID). BRZ (Austria’s federal computing center) states that credential data is stored on the user’s device and that the eAusweise app is designed for offline use, with driver’s license data usable offline for up to three months after retrieval.

Source: https://www.id-austria.gv.at/en/verwenden/eausweise

This is important because it paves the way for two separate verification models:

ISO-based (offline verification for third parties): Encrypted data is transferred between the devices via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) and verified on the verifier’s device, explicitly referencing ISO 18013-5 for the offline check.

Non-ISO (online verification by the police): An officer scans a QR code and uses an identifier in it to retrieve driver’s license data directly from the driver’s license register onto the officer device via the police app. In many ways, this is closer to a registry look-up verification than an ISO mdoc peer-to-peer presentation.

How verification works (in accordance with ISO)

Many verifier deployments keep one reader stack for both mobile credentials and physical documents. That keeps operator training consistent and preserves a fallback when a phone credential is unavailable.

A reader-side ISO mdoc check is easiest to understand as a short sequence that begins before the holder arrives:

Step 1: Reader readiness

Before any transaction, the verifier environment is set up with:

Transport capability: Proximity transactions rely on Bluetooth, NFC, or both. Reader apps need OS permissions and platform entitlements for those radios.

A trust store: Offline validation depends on issuer trust anchors being present locally, plus any intermediate certificates and revocation material a program expects.

Request presets: Mature deployments define fixed request templates tied to certain scenarios, keeping disclosures minimal.

Retention intent: Many reader systems track how long specific fields are meant to be retained.

The American case also points toward reader authentication for optional fields, stating that the holder should require reader authentication before releasing elements that are not mandatory in the ISO mDL data set table.

Step 2: Device engagement

In proximity mode, the session begins with device engagement, usually by scanning a QR code or tapping via NFC. Engagement shares session parameters and transport options, not the license attributes themselves.

Engagement ties a specific holder device to a specific reader session and provides the ingredients for session keys.

Step 3: Reader’s data request

After engagement, the reader sends a request that names the needed data elements. This is selective disclosure in practice.

In real deployments, the request is rarely built ad hoc. It is pulled from a preset:

An age-restricted sale preset might ask for an age threshold result or the smallest set needed for age calculation.

An identity verification preset might ask for name, date of birth, and portrait.

A driving privilege preset might ask for class and restriction-related elements.

This request design is one of the biggest operational choices a relying party makes. It shapes privacy impact and interoperability risk.

Step 4: Consent and data retrieval

The holder reviews the request and approves sharing; most wallets gate the approval behind a local device check such as PIN or biometrics. If the program uses reader certificates, this is also where the wallet can validate that the reader is authorized to request certain optional elements before the disclosure proceeds.

After consent, the holder device returns the requested elements plus the signed structures needed for validation with the help of BLE or NFC.

Step 5: Validation turns a response into a trusted result

Validation is where signals become reliable information for verifiers. Readers generally evaluate four things:

Issuer authenticity: The reader validates issuer signatures and builds a certificate chain to a trusted anchor, confirming that the issuer is legitimate and that the signed data has not been altered since issuance.

Element integrity: Selective disclosure only works if each disclosed element is cryptographically tied back to what the issuer signed. This is commonly done through the Mobile Security Object (MSO), described in the guidance as the structured dataset that lets a verifier authenticate other mDL elements received during the transaction.

Session binding: The reader checks that the response belongs to the session created during engagement, which reduces replay risk.

Validity windows and update expectations: Time fields such as validFrom, validUntil, and expectedUpdate are checked to reject expired credentials and to interpret update expectations in offline workflows.

Step 6: Results are packaged for operators and systems

After validation, the reader stack typically returns:

Normalized text attributes, mapped into a consistent schema for downstream systems.

Portrait imagery for in-person post-match checks.

Explicit status flags, commonly including derived age-check outcomes.

This packaging layer makes mDLs usable under real conditions. It supports clear operator prompts and auditable failure reasons, such as “expired,” “issuer authentication failed,” “consent declined,” or “transport timeout.”

How Regula supports mobile driver’s license verification needs

2026 is expected to bring a broader mDL rollout in the US and abroad. As adoption grows, more and more verifiers will look for a reader implementation that covers the full ISO mdoc flow end to end, then returns results in a format that staff and backend systems can use.

These implementations can be powered by Regula Document Reader SDK, which will provide you with:

Session-based mDL reading: The SDK starts and manages a full mDL verification session by handling device engagement, and then running data retrieval within that same session.

Flexible mDL data retrieval: The SDK supports retrieving mDL data over BLE or NFC so verifier apps can use the transport that fits their checkpoint and device constraints.

Trust material as a first-class setup item: The SDK lets verifiers load the trusted certificate material needed for issuer authentication (including CBOR PKD resources, with CSCA/DSC chains for NFC access and issuer certificate chains for BLE retrieval).

Controlled data requests: The SDK lets verifiers request only the needed mDL data elements using request presets, while also setting per-field intent-to-retain.

Well-packaged results: The SDK returns normalized text and graphic results plus clear status outcomes, including overall mDL validation and built-in age-check results.

Have any more questions? Contact the Regula team now — we are here to help!

.webp)