According to the United States’ Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), fiscal year 2023 saw over 1.3 million suspicious activity reports (SARs) filed on the basis of structuring.

Structuring still remains a low-tech but highly effective tactic for placing illicit cash into legitimate financial channels (money laundering) without triggering reporting rules. And the reason it is so effective is that it often falls under the radar: without strong KYC procedures and rigorous transaction monitoring, detecting it is very difficult.

In this article, we will explain what structuring in money laundering is, map a common operational scheme step by step, provide practical examples, and explore how it can be countered.

Get posts like this in your inbox with the bi-weekly Regula Blog Digest!

What is structuring in money laundering?

Structuring, in the context of anti-money laundering (AML), is the deliberate design of deposits, withdrawals, transfers, or purchases so that each falls below a certain reporting or recordkeeping threshold.

In the United States, the most familiar legal trigger is the $10,000 currency reporting rule: a cash deposit or other currency transaction that exceeds $10,000 in a single business day requires a currency transaction report. That’s why a pattern of sub-$10,000 deposits meant to defeat that obligation can be classified as structuring. Structuring in AML is viewed as the intentional evasion of statutory rules, and financial institutions must report suspicious activity when they detect it.

Structuring is also considered illegal in many jurisdictions as it is an intent to evade statutory triggers—and even if funds are lawful, they do not make evasion lawful.

How does money structuring work?

To answer that question, let’s examine the operational template that investigators and compliance analysts see most often:

Step 1. Collection: Criminal actors gather large volumes of cash from illicit activity; now their goal is to introduce that cash into regulated channels with minimal traces.

Step 2. Fragmentation into packets: Cash is divided into smaller amounts designed to remain below reporting triggers (such as the $10,000 threshold) or the identity-collection trigger for monetary instruments. These packets are prepared to be moved by people or devices. This is the core of financial structuring.

Step 3. Assignment to vectors and couriers: The packets are allocated across several entry vectors: multiple couriers, multiple new accounts, different branches, retail cash services, ATMs, money orders, prepaid product loads, or remittance agents.

Step 4. Time/amount shaping: Deposits are scheduled to avoid single-day aggregation that would produce a CTR. Amounts are varied slightly to reduce obvious repetition, but the aggregate value is often large.

Step 5. Consolidation through funnel accounts: Once in the system, funds are moved from pass-through accounts into consolidation accounts by wires, internal transfers, or check clearing. From there, payment rails carry funds outward, often cross-border.

Step 6. Normalization or layering: Final movements attempt to create the outward appearance of commercial payments, payroll, or legitimate remittances. If detection occurs earlier, the actors may pivot to cash-outs or quick withdrawals.

Luckily for compliance teams, each stage creates markers they can pick up on: odd timing, repeated sub-threshold amounts, linked IDs, clustered device fingerprints, or rapid onward transfers to a narrow set of beneficiaries. We will discuss these in greater detail in one of the following sections.

What is the difference between smurfing and structuring?

These two terms aren’t easy to compare and contrast, since they are very closely related, with a fair amount of overlap. The basic difference between smurfing and structuring can be described as follows:

Structuring is the legal term and the compliance trigger. It describes the intent and the fact of regulatory evasion, for example, designing deposits to avoid currency transaction reports.

Smurfing is the operational method for implementing structuring. It uses multiple accounts and many couriers to fragment flows. Smurfing can be low-skill and large-scale: while smurfers act to defeat reporting and recordkeeping duties, their actions constitute structuring.

For a more detailed breakdown, see the following table:

Criterion | Smurfing | Structuring |

|---|---|---|

Nature | Practical method—who/what/where: couriers, many accounts, various entry channels (ATMs, retail, remittances). | Broader legal/compliance notion—asks whether transactions were arranged to avoid statutory triggers. |

Required element to label it | Observable multiplicity: many small deposits/transfers, multiple actors/accounts, repeated timing. | Intent to evade reporting/recordkeeping is decisive; circumstantial evidence is used to infer intent. |

Typical actors | Organizer(s) and couriers, or many unrelated-looking depositors. Often labor-based. | Could be a single actor or a ring; legal focus is on the actor(s) who planned or encouraged evasion. |

Scale | Often high-volume but fragmented across many entries (large aggregate value hidden in many small items). | Scale is secondary; even small aggregates can be structuring if designed to evade a trigger. |

How it is proven | Map networks (accounts, devices, phones, beneficiaries), show coordination and flow from many couriers to common recipients. | Combined transactional pattern with behavioral or documentary evidence that supports intent. |

Example | 20 couriers each deposit $4,800 in different branches; soon wired to a single beneficiary. | One person deposits $9,900 five times after asking staff what amount triggers a report—clear evidence of intent to evade reporting. |

Structuring examples and red flags

Now let’s examine three of the most commonly observed patterns of structuring in banking, and what can tip off regulators in each case:

Example 1: One person, split deposits

Over a seven-day period, a single customer makes in-branch cash deposits into one retail checking account at three different branches of the same bank in the same metro area.

The payment breakdown could look as follows:

$6,000 on Monday (Branch A)

$6,500 on Wednesday (Branch B)

$5,800 on Thursday (Branch C)

$6,200 on Saturday (Branch A)

$5,700 the following Monday (Branch B)

Total deposited in 10 days = $30,200.

The account then wires the entire sum in two payments to a single beneficiary account in another state two days after the last deposit.

Red flags

Rolling sum of cash deposits for that customer that is larger than the internal threshold.

Repeated use of deposit amounts always under $10,000.

Deposits at multiple branches in quick succession.

Rapid outbound wires to a single beneficiary shortly after aggregation.

Example 2: Smurfing with device correlation

Ten newly created retail deposit accounts are opened online over a two-week period. Each account is funded within three days of opening by deposits of $4,500 placed at local ATM kiosks or by couriers in person. Within one week, each account wires $4,200–$4,400 to the same beneficiary account.

The onboarding logs show that all ten accounts were created from the same device fingerprint and a small set of related IP addresses. Phone numbers provided for account notifications are prepaid numbers that resolve to the same forwarding service. Several ID documents submitted at onboarding appear genuine at first pass, but image analysis shows re-use of the same photo cropped into different ID templates.

Red flags

Multiple new accounts with deposits shortly after opening.

Wire transfers from those accounts to a single beneficiary or a small set of beneficiaries.

Shared device fingerprints/IP addresses at onboarding.

Reuse of the same photographic image across different IDs.

Example 3: Smurfing via non-bank channels

Money transfer operators and other money services businesses (MSBs) process very large volumes of low-value payments and use global agent networks. Those features make MSBs an attractive vector for placement of cash through structuring and smurfing.

Criminal schemes exploit these channels because they:

allow fast cash-out in high-volume remittance corridors;

rely on local agents whose onboarding quality and AML controls can vary;

create complex correspondent chains that delay cross-border matching of suspicious patterns.

For example, a remittance agent receives several small payout requests for the same city and the same beneficiary within 48 hours. The senders overseas claim they wired funds through normal routes. Locally, an unrelated person presents a legitimate ID and collects the payout on behalf of the beneficiary.

Later tracing shows the cash paid out at the agent came from criminal sources substituted into the payment chain, while the original overseas remittance was rerouted or intercepted elsewhere.

Red flags

Multiple small payout requests for the same beneficiary or location within a short window.

A mismatch between originator details and the identity of the person who collects the funds.

Unexpected intermediary agents or routing steps in the payment chain.

Rapid series of payouts from different senders all directed to the same local payout point.

Two main methods of structuring prevention

Structuring detection rests on two big pillars: continuous transaction monitoring and strong KYC. In this section, let’s take a closer look at both and see how these measures protect organizations from this hard-to-detect technique.

Why transaction monitoring matters

Transaction monitoring (TM) pulls transactions together across time, accounts, branches, agent networks and product types, and then surfaces clusters that meet certain risk thresholds. In essence, TM is the core reason why sets of sub-threshold cash deposits eventually become reportable as structured activity.

A well-tuned TM system provides analysts with pre-assembled evidence: timelines, aggregated sums, counterparty graphs, and itemised suspicious events.

How transaction monitoring delivers value

Transaction monitoring reduces structuring risks in the following ways:

Early detection through aggregation and temporal rules

TM computes rolling aggregates (for example, 7-day or 30-day totals) and flags accounts that accumulate cash above internal thresholds even if no single deposit breached a statutory limit. It also detects clusters of deposits near statutory triggers, repeated branch or agent use, and quick onward transfers.

Network analysis and entity resolution

Network views produce the “many deposits, one operator” picture investigators need. TM engines link accounts to shared attributes: common beneficiary accounts, device fingerprints, IP addresses, agent IDs, telephone numbers, and reused document images. Graph analytics then surface hub-and-spoke patterns typical of smurf rings.

Triage and prioritisation for human analysts

Analyst time is scarce; luckily, TM can score alerts by risk and by evidential richness, giving higher priority to clusters that include rapid consolidation, cross-border wires, or corroborating identity linkage. Good systems reduce false positives by combining transaction patterns with identity signals, sanctions hits, and customer risk levels.

Why IDV/KYC matters

In turn, IDV augments transaction monitoring through converting certain signals into evidence:

It raises signal quality: When an alert contains face hashes, document image hashes, or device fingerprints, analysts can move quickly from “suspicious pattern” to “same person or ring.”

It blocks rapid consolidation: If TM flags aggregated sub-threshold deposits, an automatic step-up verification that re-checks identity at the teller, agent, or via an authenticated remote flow can interrupt movement of funds before they are wired away.

It improves SAR value: A SAR that bundles timelines, transaction graphs, and identity artifacts is far more actionable for investigators. Explicit identity linkage helps show the design element behind structuring, which is often decisive in enforcement reviews.

That’s why strong IDV/KYC at account opening, combined with ongoing customer due diligence (CDD), raises the cost and complexity of running this operation. When a bank verifies identity details and establishes a baseline risk profile, it can detect sooner if an account classified as low risk starts to act like a high-volume cash courier and escalates for review.

Customer due diligence also means collecting documented information on the source of funds and the intended use of the account. A person who reports modest salaried income but begins making large cash deposits creates a clear discrepancy that demands follow-up. For customers with elevated risk (e.g., politically exposed persons), enhanced due diligence applies and transaction monitoring gets even more intensive.

That is why many regulators instruct financial institutions to verify identities and re-verify when risk rises; for example, the CDD Rule makes identity proofing a foundational control for preventing many forms of structured currency movement.

How IDV/KYC delivers value

Now let’s explore the AML identity verification features that reduce the risk of currency structuring:

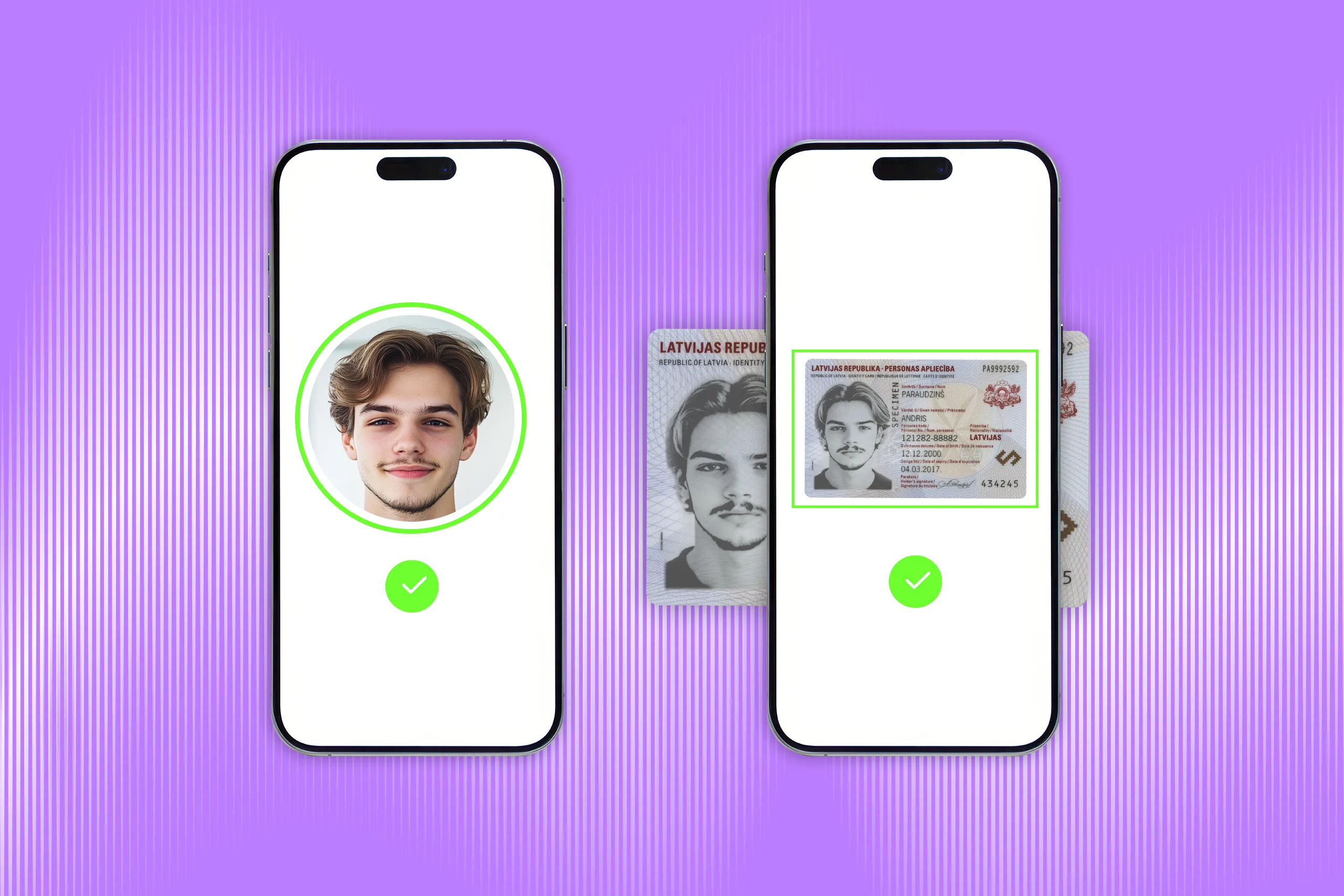

Document authenticity checks (for physical IDs)

Attempts at financial structuring often involve using counterfeit or recycled IDs to open multiple accounts. If a document reader finds repeated image hashes or the same underlying photo used in different templates, that is strong evidence of multiple accounts linked to one face.

Luckily, an IDV solution can perform a vast array of authenticity checks: verifying the RFID chip with the document owner’s biometric stored inside, as well as physical security features like holograms, UV inks, and microprint.

Biometric face matching with liveness checks

Equally important is comparing a live selfie to the photo on the ID (1:1 face comparison) and storing a template or image hash for a cross-check against a database (1:N face identification). This also helps identify a single person opening multiple accounts under different names.

What’s more, liveness detection has now become an integral part of face recognition: it confirms that a real person is present in a selfie, as opposed to static face images, video replays, masks, or even deepfakes.

Step-up verification workflows

If a customer starts making multiple sub-threshold cash deposits, the system can automatically require reverification before funds are consolidated or wired. That prevents easy consolidation and creates an audit trail showing that the bank challenged the actor.

A step-up can require live video verification, additional ID documents, or in-branch biometric capture.

Boost your anti-structuring KYC procedures with Regula

When done correctly, ID verification can complement the capabilities of transaction monitoring systems and serve as a barrier between financial institutions and structuring. And even if crime does slip through the cracks, the system will help build an evidential chain post-mortem to the person or network behind the deposits. This chain can then support a strong suspicious activity report and give law enforcement a reproducible lead.

A solution like Regula IDV Platform is a one-stop-shop for all KYC needs for banks, fintechs, and other financial institutions.

As a true turn-key solution, Regula IDV Platform will provide you with:

Identity lifecycle management with flexible orchestration and tailored workflows across every stage of the user journey.

Complete document and biometric verification, backed by the biggest template database in the world (16,000 documents from 254 countries and territories).

Instant facial recognition with liveness detection, preventing the use of static face images, printed photos, video replays, video injections, or masks.

AML/PEP screening, as well as validation against trusted global databases.

User data management and analytics for continuous monitoring.

Smooth integration with your existing tech stack via flexible connectors.

Let’s drive the future—together. Book a call to learn more about our solutions!