It is simply impossible to imagine document examination without ultraviolet light sources: from ordinary users to forensic document examiners, everyone relies on ultraviolet (UV) examination of documents or banknotes.

But have you ever considered how the choice of UV source can influence the results?

In this article, we will examine the two most common ultraviolet light sources — the UV lamp and the UV LED — and explain the fundamental differences that matter to specialists.

Let’s go through the details step by step.

What is fluorescence?

Fluorescence is a physical phenomenon where a material absorbs light of a shorter wavelength (usually ultraviolet) and immediately emits light at a longer wavelength (typically visible). This emitted light appears as a glow and disappears instantly when the excitation light is removed.

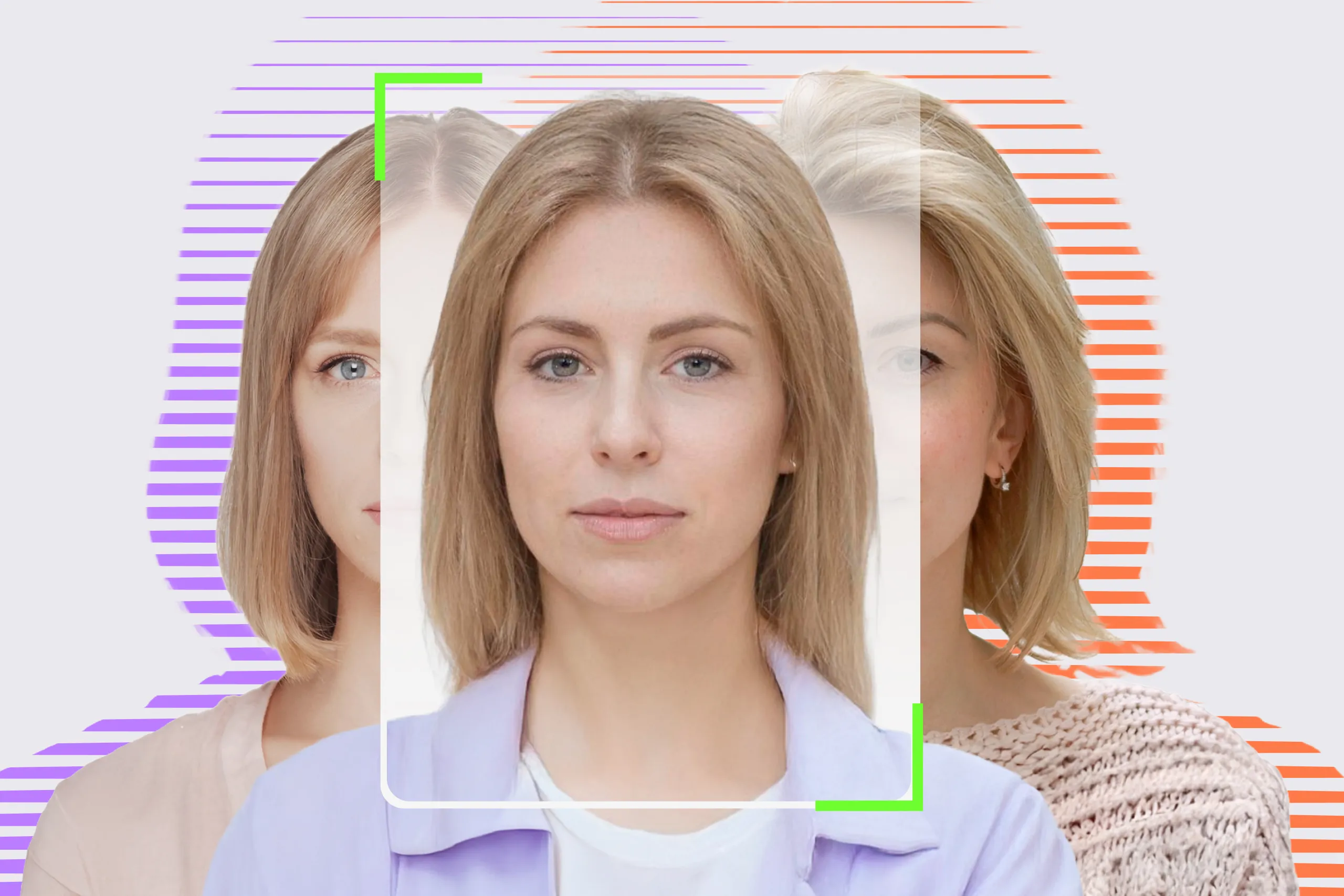

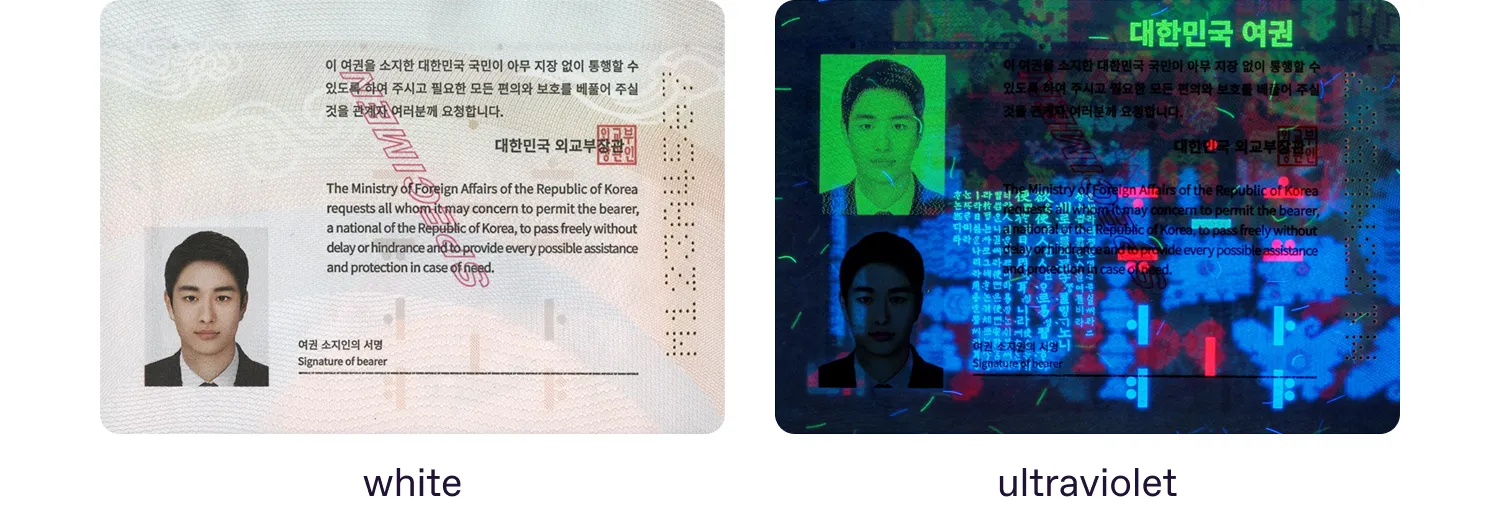

Passport of South Korea issued in 2021 under white and ultraviolet light.

In identity documents, fluorescence under UV light is one of the most widely used security features, and it operates in two main ranges:

Long-wave UV-A — 365 nm

Short-wave UV-C — 254 nm

Less commonly, but still used, is UV-B, which in security documents is typically represented by 308-313 nm wavelengths depending on the document manufacturer.

Identity card of Poland issued in 2021. The UV pattern changes its colors from blue under 365 nm wavelength to pink under 313 nm.

To examine the ultraviolet fluorescence of identity documents, specialists use special devices — magnifiers, document readers, manual control devices, or video spectral comparators — equipped with ultraviolet sources using light of different wavelengths.

The source itself can be either a traditional UV lamp or a UV LED. They both serve the same purpose, but how do they affect the examination results?

Subscribe to receive a bi-weekly blog digest from Regula

LEDs vs. lamps

LEDs and lamps (for example, low-pressure mercury lamps) have a number of differences when it comes to operating in the ultraviolet range, especially around 254 nm. Here are the main differences:

| Parameter | LEDs | Lamps |

|---|---|---|

| Emission mechanism | Emission occurs due to the recombination of electrons and holes in a semiconductor material. For UV LEDs, special materials like aluminum and gallium nitrides are used. | They emit UV light through a mercury discharge. Mercury atoms become excited, and when they return to the ground state, a photon of 254 nm is emitted. |

| Efficiency | Usually have high energy efficiency because most of the energy is converted into light. | Efficiency can be lower due to heat losses and the need to warm up the lamp to create the discharge. |

| Size and shape | Compact and easy to integrate into different devices. Their shape and size can vary widely. | Usually bulkier and require a special design to maintain the discharge. |

| Turn-on time | Turn on almost instantly and reach full brightness right away. | May need time to warm up before reaching full brightness. |

| Lifespan | Usually have a long service life, often more than 10,000 hours of operation. | Lifespan can be much shorter and depends on operating conditions. |

| Temperature stability | Can operate in a wider temperature range and are less sensitive to temperature changes. | Sensitive to ambient temperature and may require additional cooling or heating. |

| Environmental impact | Do not contain mercury or other harmful substances, so they are less harmful to the environment. | Contain mercury, which requires special disposal procedures. |

These differences make LEDs preferable in many applications, especially where compact size, long lifespan, efficiency, and environmental safety are important. However, 254 and 313 nm lamps are still used in document authentication devices due to their low cost.

But the differences between LEDs and lamps operating at 254 nm do not end there. They also differ in:

Spectral emission width

Spectral purity

Wavelength stability

Let’s consider each point one by one.

1. Spectral emission width

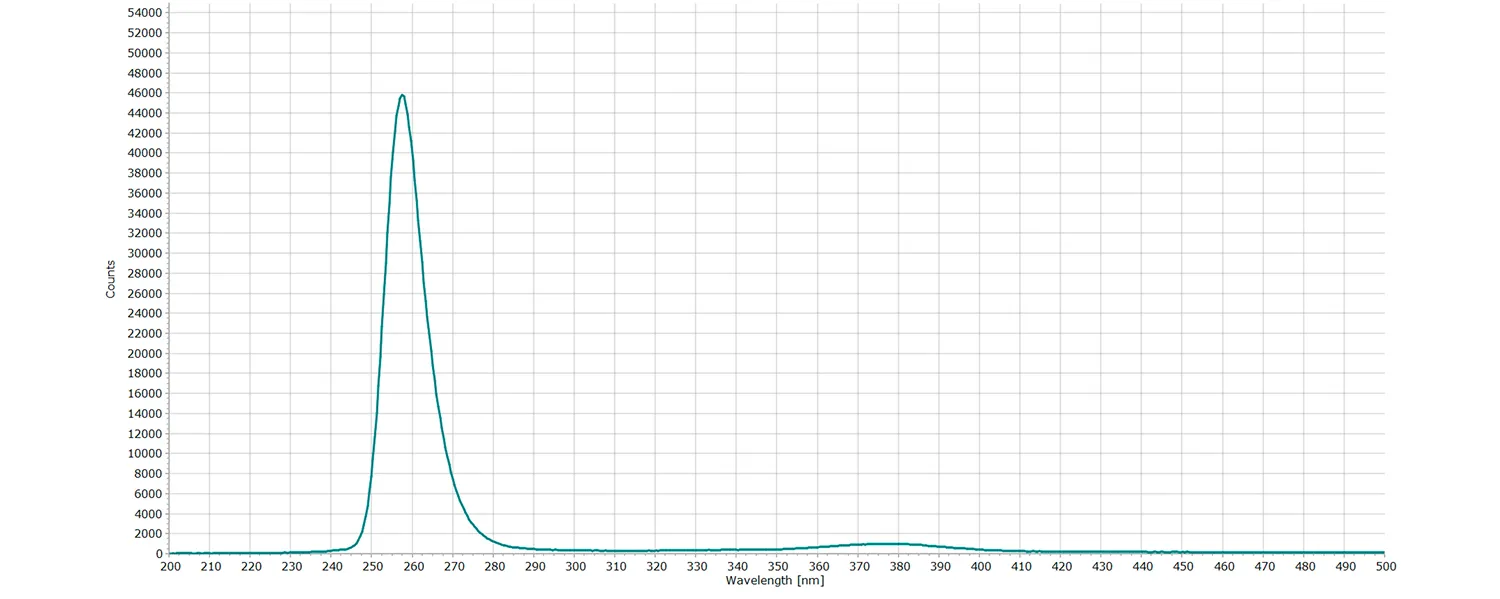

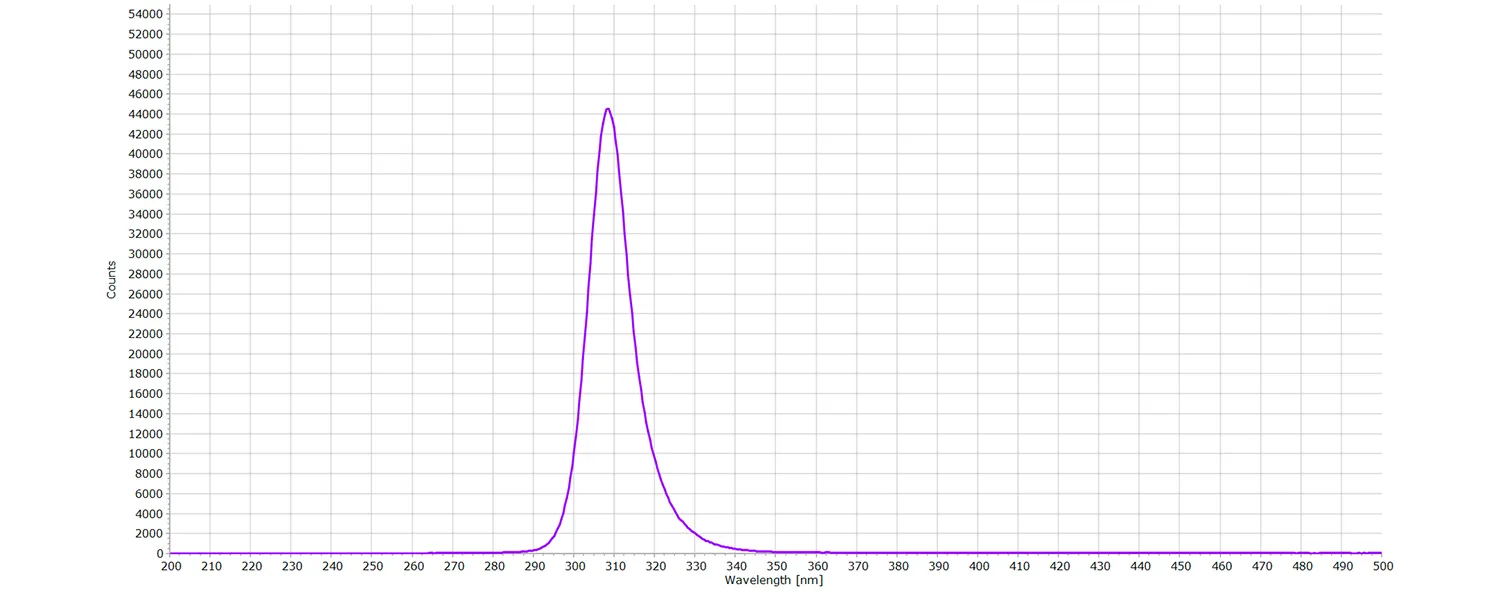

LEDs usually emit light in a narrow wavelength range. For example, a UV 254 nm LED will emit mainly within a small spectral band around that wavelength, with a typical full width at half maximum (FWHM) on the order of ~15 nm. The emission spectrum of LEDs is very narrow, which allows them to produce almost monochromatic light.

Emission spectrum of a 254 nm LED. No measurable parasitic peaks in the measured range.

Emission spectrum of a 313 nm LED. No measurable parasitic peaks in the measured range.

Because UV LEDs can have minor stray emission in the visible range, we use optical filters to suppress visible light and keep the illumination band as clean as possible.

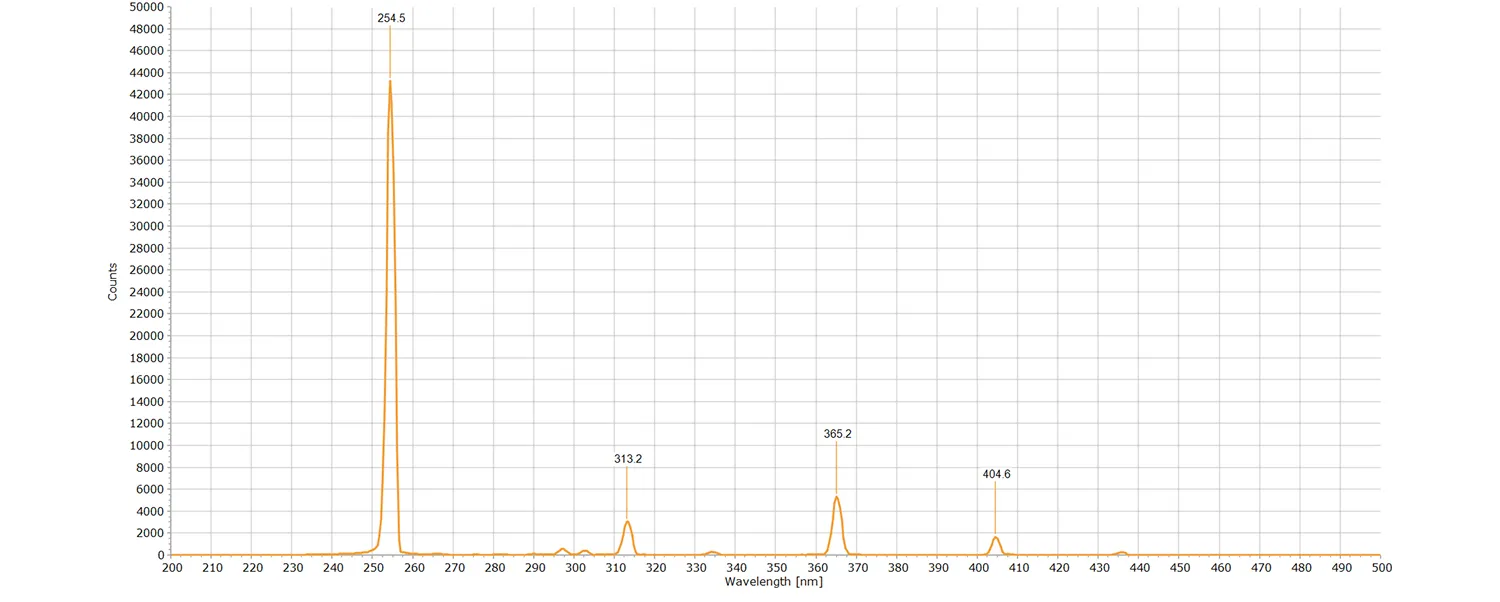

Low-pressure mercury lamps used to generate UV radiation at 254 nm have spectral lines related to transitions in mercury atoms. The main line at 254 nm is quite narrow, but the lamp can also emit other lines in both the UV and visible range. Mercury lamps have several discrete lines in the spectrum, making their spectral emission more complex.

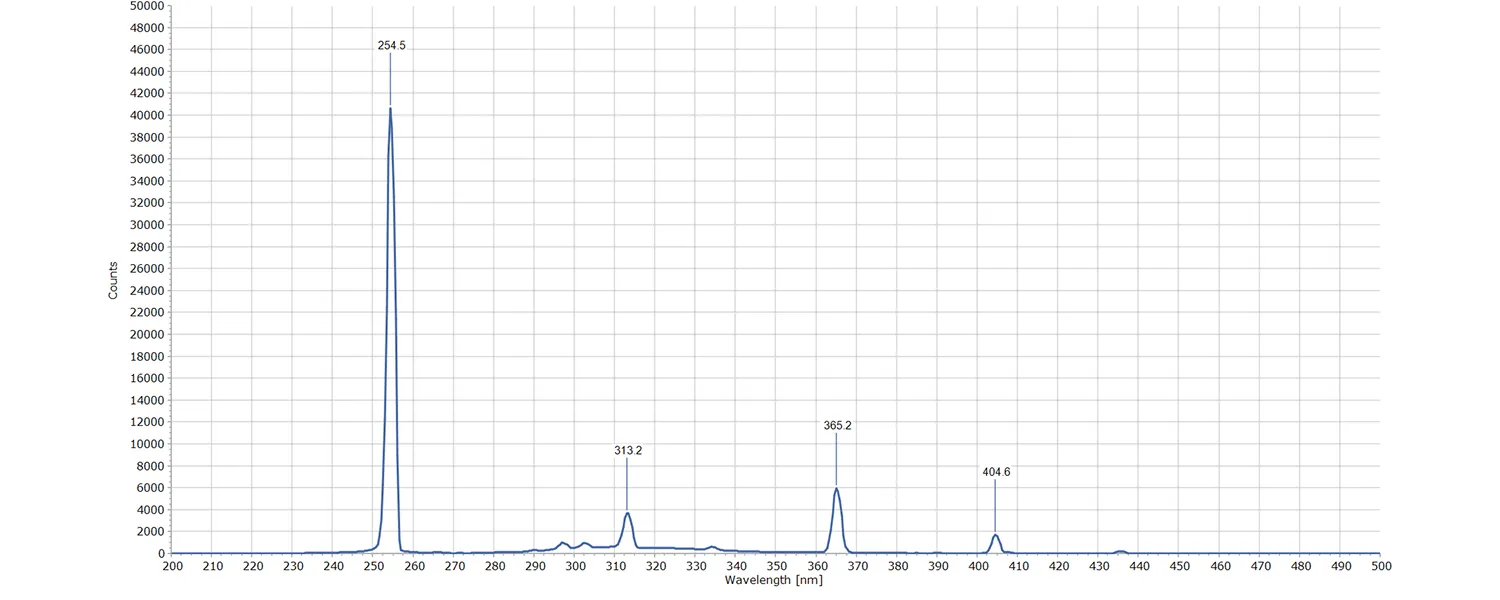

Emission spectrum of a 254 nm lamp. Parasitic spectral peaks at 313, 365, and 405 nm wavelengths.

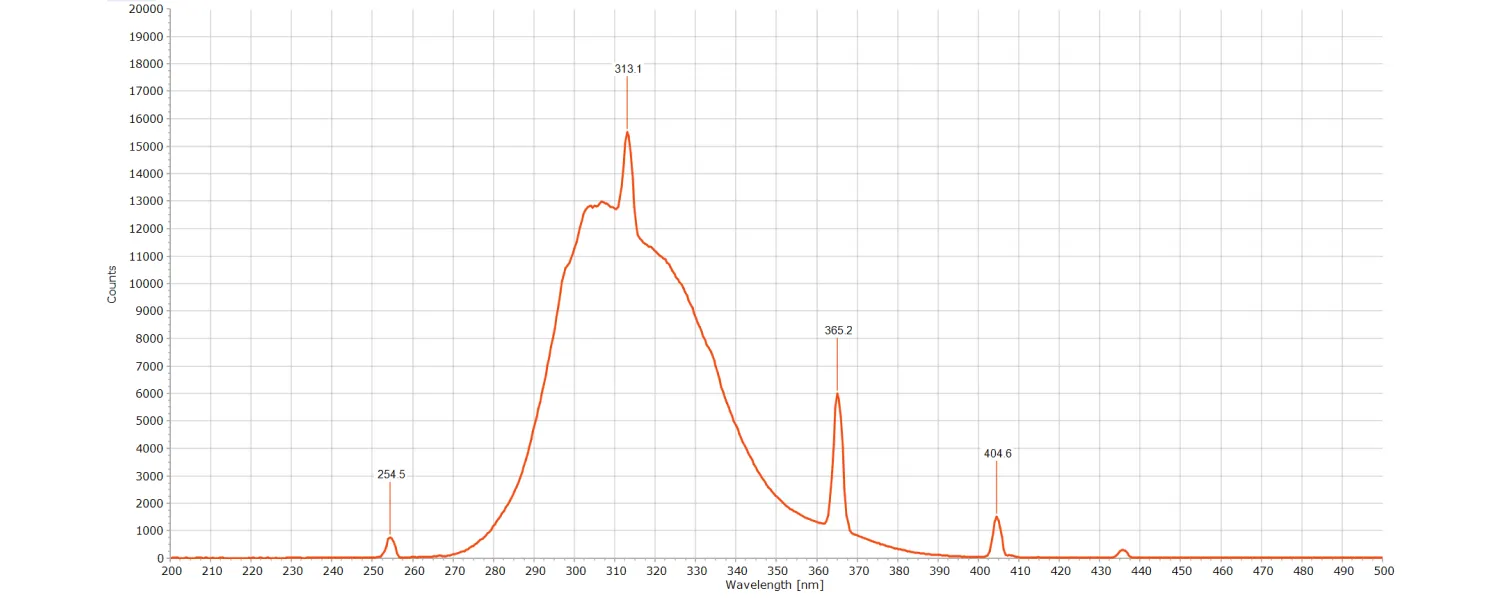

This graph demonstrates the emission spectrum of a 313 nm lamp. Parasitic spectral peaks at 254, 365, and 405 nm wavelengths.

This graph shows the emission spectrum of an activated 254 nm lamp alongside a nearby 313 nm lamp that is not switched on. The 313 nm lamp nevertheless exhibits slight fluorescence due to excitation by the active 254 nm lamp.

As you can see, all three graphs of UV lamps show the same repeating pattern: the presence of parasitic spectral peaks. For the 254 nm UV lamp it's 313, 365 and 405 nm, and for the 313 nm UV lamp it's 254, 365, and 405 nm, respectively. These parasitic emissions can excite fluorescence at other wavelengths.

2. Spectral purity

Based on the previous paragraph, we can see that LEDs provide high spectral purity and a narrow emission peak, which makes them ideal when you need to selectively excite a specific security feature and avoid unintended fluorescence from neighboring bands.

Although mercury lamps deliver strong emission at 254 nm (narrow peak), they may also emit additional wavelengths, which can be undesirable in some applications.

3. Wavelength stability

LEDs have high wavelength stability as long as the current and temperature are kept stable.

Mercury lamps can show small wavelength fluctuations due to changes in pressure and temperature inside the lamp.

Now, bearing in mind the features and spectral characteristics of UV lamps and UV LEDs, it is worth moving on to an important aspect — the object of examination, namely, the material from which it is made.

Why are polycarbonate and ultraviolet not friends?

Most modern identity documents are either entirely polycarbonate (driver’s licenses and ID cards) or incorporate a polycarbonate data page (passports). The choice in favor of polycarbonate was made because it is durable, quite resistant to heat, moisture, and mechanical stress, and supports the integration of advanced security features, making counterfeiting significantly more difficult.

But due to its composition, polycarbonate strongly absorbs deep‑UV; below ~300 nm (especially at 254 nm) transmission is extremely low. The light simply cannot penetrate the layers of the document to excite any fluorescent inks or fibers inside. So, even if a document contains patterns printed with the use of ultraviolet inks that glow under 254 nm wavelength, they will not become excited because of polycarbonate.

Passport of Georgia issued in 2025. The document glows under UV-A and UV-B spectral ranges, but shows no fluorescence under UV-C.

As a result, identity documents — whether they contain a polycarbonate insert or are made entirely of polycarbonate — cannot feature glowing patterns visible under ultraviolet light at 254 nm. All UV-reactive security features in such documents are designed to respond only to UV-A and UV-B light, around 365 and 313 nm.

Tricky ultraviolet light

But let’s imagine you come across an image of a modern polycarbonate document photographed under UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C light — something that seems to contradict everything we’ve just discussed. How can that be, if polycarbonate does not transmit UV-C light at all?

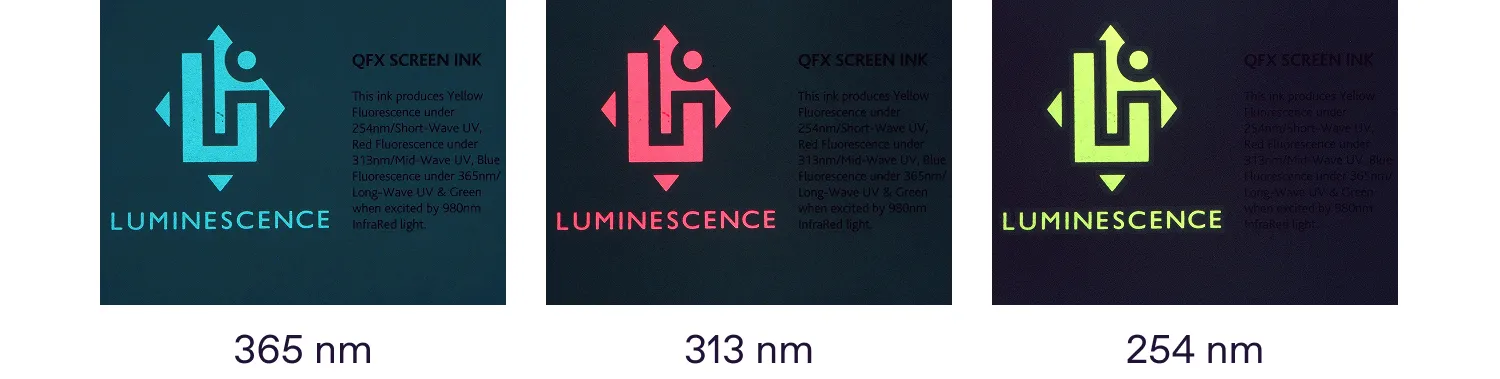

We did an experiment with a QFX screen ink sample card, which is made of paper and contains applied inks that react to UV 365 nm (blue), UV 313 nm (red), and UV 254 nm (yellow).

In the first round, we captured an ink sample card as it is using LED ultraviolet lights.

Images taken using the Video Spectral Comparator Regula 4306. The fluorescence behaves as described by the manufacturer.

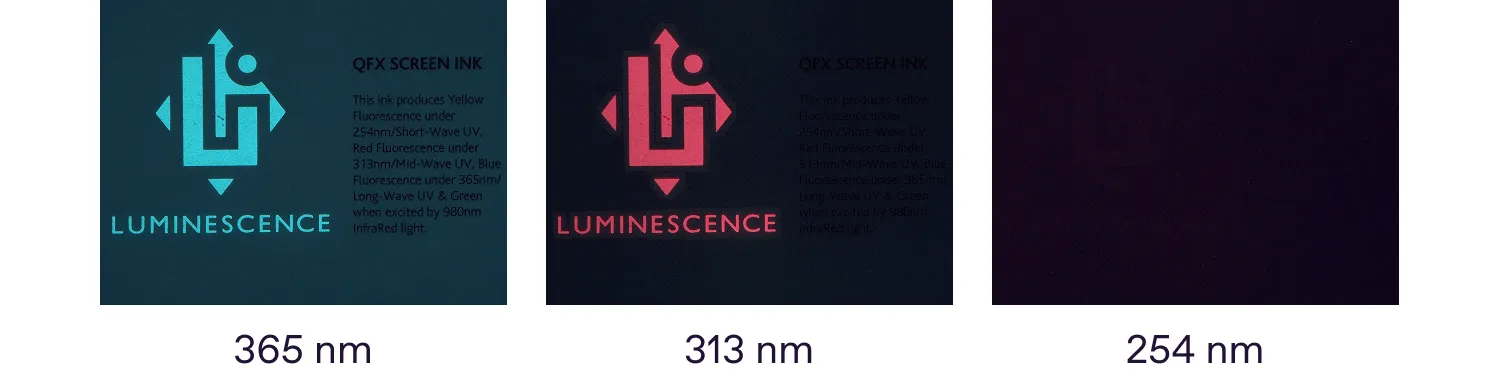

Then, we covered the ink sample card with a polycarbonate film of 200-micron thickness.

Images taken using the Video Spectral Comparator Regula 4306. The fluorescence at 254 nm wavelength disappears as the film shows itself as a cutoff filter for all wavelengths below 300 nm.

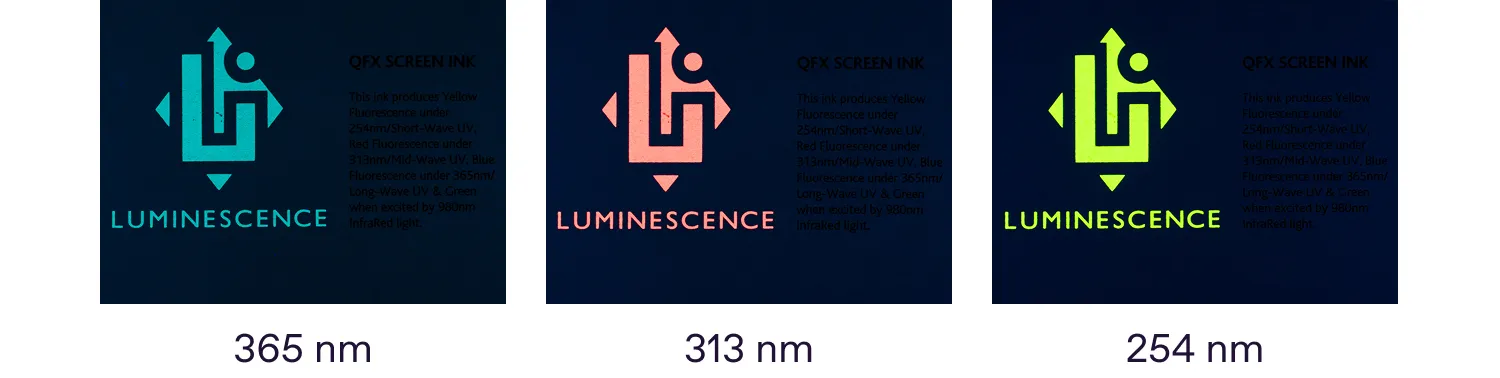

Then we repeated the same procedures, but using ultraviolet lamps.

In the first row there are images taken under ultraviolet lamps of different wavelengths.

Fluorescence of uncovered paper sample card at different UV ranges is equal to LED.

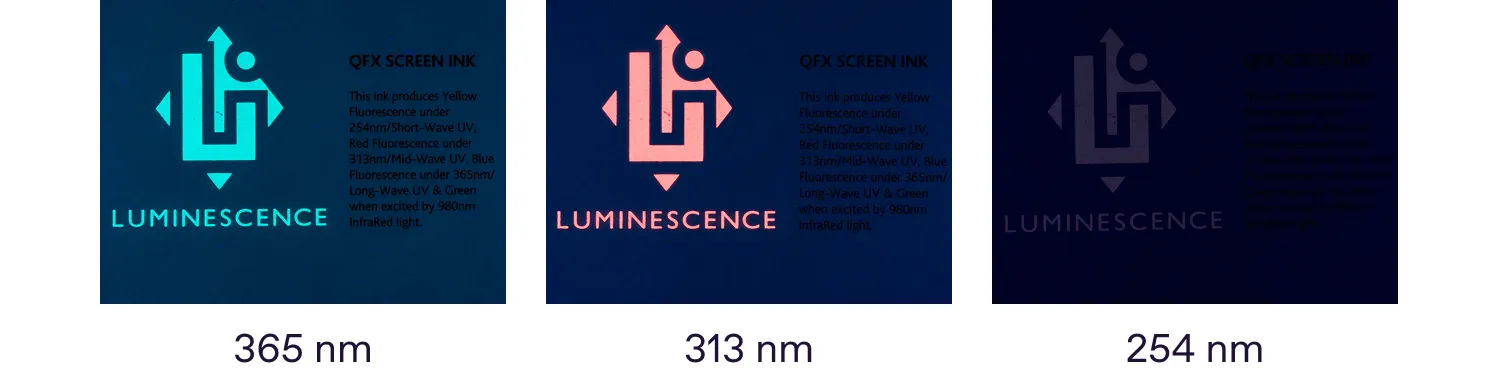

Now let’s see the covered ink sample card with a polycarbonate film of 200-micron thickness.

At a 254 nm wavelength, the UV image is visible due to the non-monochromatic radiation of the lamp. The image appears as a reaction to 313 and 365 nm radiation.

Our experiments show that under 254 nm UV illumination produced by an LED light source, no fluorescence is observed from UV inks covered with polycarbonate. However, when UV lamps are used, weak but still distinguishable fluorescence is detected.

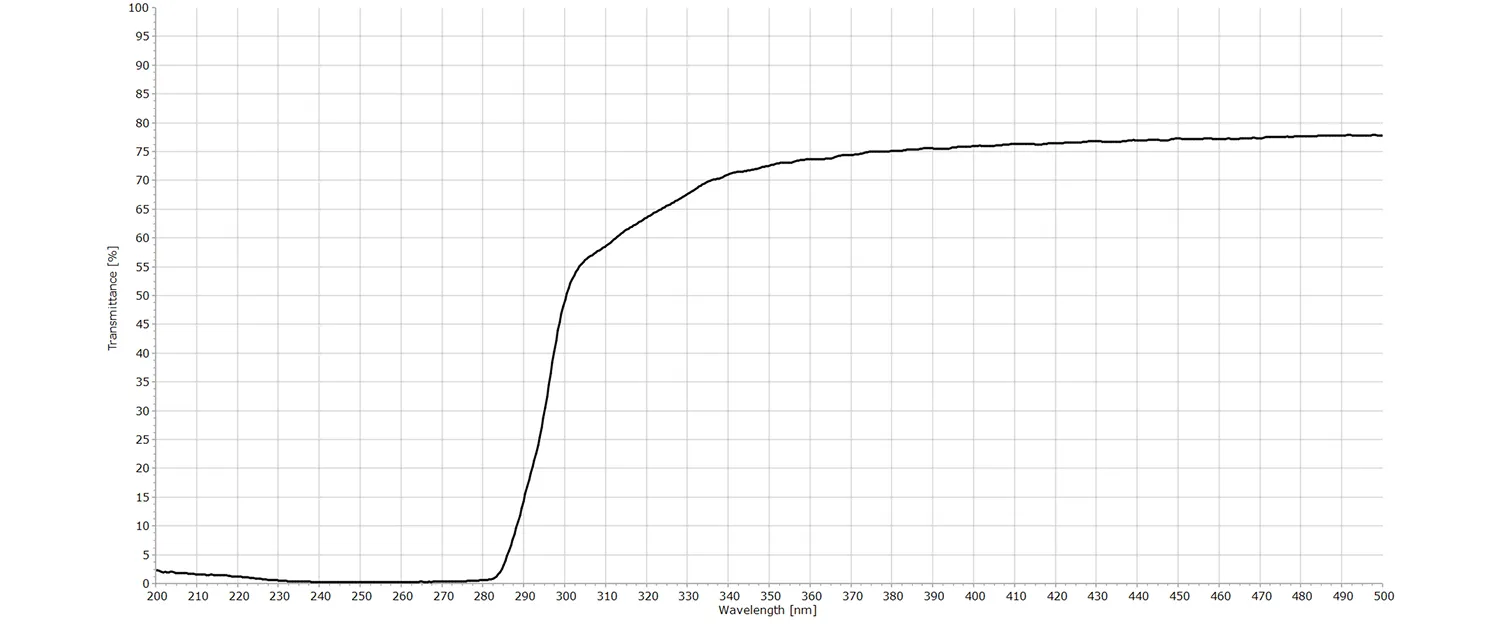

To explain this phenomenon, we needed to create a graph that demonstrates the transmission spectrum of 200-micron thick polycarbonate.

The transmission spectrum of polycarbonate shows that it effectively acts as a filter, blocking UV-C radiation. The transmission border can be around 280 nm (depending on the polycarbonate manufacturer).

In other words, if an object printed with inks designed to luminesce under 254 nm is covered with a polycarbonate laminate, the excitation radiation will not reach the inks: it will be absorbed within the polycarbonate layer.

As we noted earlier, there are parasitic spectral peaks at 313, 365, and 405 nm in the graph of the emission spectrum of a 254 nm lamp. Since polycarbonate does not transmit ultraviolet radiation below 280 nm but does allow the passage of wavelengths above this threshold, ultraviolet patterns tuned to the 313 nm and 365 nm bands can still be excited and glow. This effect can create the false impression of fluorescence induced by UV-C light, when in fact it is caused by these higher-wavelength parasitic emissions.

And in fact, if we combine an image under 365 nm, which glows blue, and an image under 313 nm, which is predominantly red, we get a mixed response (purple glow) driven by the lamp’s 313 nm and 365 nm parasitic lines (blue + red = purpl). This further confirms that in the example we are considering, we are seeing a fake glow under 254 nm which is a weak glow of the excited UV-A and UV-B inks.

What conclusion can we make?

The emission spectrum of LEDs is very narrow, meaning they do not excite neighboring wavelengths. In contrast, ultraviolet lamps of 254 nm have a non‑monochromatic output due to additional spectral lines, which can cause a “false” excitation of UV fluorescence at wavelengths above 300 nm. This is important because “true” ultraviolet fluorescence at 254 nm is impossible to observe when dealing with polycarbonate materials, as the substrate does not transmit light in that range.

Key takeaways

UV LEDs provide narrowband illumination with high spectral purity.

UV lamps can emit additional spectral lines that unintentionally excite UV‑A/UV‑B features.

For polycarbonate documents, apparent ‘254 nm fluorescence’ can be a false effect caused by parasitic emissions above the cutoff

Why Regula believes in LEDs

Regula has been integrating LED light sources into forensic hardware solutions since 1998, adopting LED illuminators for new spectral ranges as soon as they became available. In 2024, the company implemented its latest transition to LED across all comparators, replacing traditional UV-B and UV-C lamps with LED sources.

As a result, the Video Spectral Comparator Regula 4306 is now fully equipped with LED illuminators, and 99% of the light sources in other Regula comparators also use LED technology.

Although LED diodes are more costly, Regula integrates them because we believe they deliver superior performance, provide more reliable results, and are more environmentally friendly.