The EU Digital Identity Wallet is arguably one of the most ambitious digital identity projects the European Union has attempted so far. It is meant to be a standardized way for every EU citizen and resident to carry official proof about who they are, what they are allowed to do, and what they can access, directly on a phone, under a single European digital identity framework.

However, with this great ambition comes great confusion. Inside specialist circles, the project triggers scepticism rather than enthusiasm, with doubts over data security, user privacy and practical value. And outside those circles, most people still have only a vague idea of what the EU Digital Identity Wallet actually is.

In this article, we will break down what exactly the European Digital Identity Wallet is supposed to do, and where things stand as of late 2025.

Get posts like this in your inbox with the bi-weekly Regula Blog Digest!

What is the EU Digital Identity Wallet?

The EU Digital Identity Wallet is a smartphone application issued or recognized by an EU Member State under the EU Digital Identity Wallet Regulation. It is a state-backed identity wallet that lets a person identify themselves, receive official credentials, and present them to online and offline services in a very controlled way.

In this model, highly trusted organizations such as population registers, driver’s license authorities, universities, social security institutions, health insurers, and, in some cases, banks or qualified trust services issue digital credentials. The EUDI Wallet then holds these credentials on the user’s device.

On the other side, relying parties (tax portals, municipal portals, car rental firms, online merchants, telecom operators, banks) request proofs from the wallet when a person wants to access their digital services or open bank accounts.

The wallet acts as the user-facing hub that connects all these roles inside the broader EU digital identity ecosystem.

What the wallet can carry

In the legal and technical texts, a European Digital Identity Wallet must at least support:

A digital identity credential (PID) that in practice has the same legal effect as a national ID card for online use.

A mobile driver’s license (mDL), including categories and restrictions.

Credentials for login and strong electronic identification for public and private portals.

Electronic prescriptions and health identifiers (linked to ePrescription and eHealth systems).

Diplomas, enrollment statements, professional licenses and certificates.

Social security documents such as EHIC data or work-related forms (for example, PD A1).

Attributes that matter for daily life, such as IBANs for bank accounts or proof of professional roles.

Travel-related credentials, such as digital travel credentials and transport tickets, are not yet mandatory in the regulation itself, but are actively being tested in the EWC pilot and related projects, and are repeatedly cited by the European Commission as a key use case for EU digital identity wallets.

Law, toolbox and reference code

The EU Digital Identity Wallet Regulation amends the earlier eIDAS framework on electronic identification and trust services. It requires every Member State to provide at least one certified EUDI Wallet and to accept that wallet for high-assurance login to banking, telecom and key public services within a fixed timeframe.

To avoid 27 different stacks, the European Commission and Member States have agreed on a Common Toolbox. The key piece is the Architecture and Reference Framework, often shortened to ARF. That framework:

Describes the architecture of the EUDI Wallet ecosystem, including roles, data flows and security requirements.

Links directly to the text of the EU Digital Identity Regulation and its implementing acts.

Profiles existing standards and protocols, such as OpenID for Verifiable Credential Issuance and Presentation.

The role of the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI)

Alongside the Commission’s own toolbox, ETSI’s Electronic Signatures and Trust Infrastructures committee provides detailed standards for the trust-service side of this ecosystem. Specifications like ETSI TS 119 411-8 and ETSI TS 119 475 spell out how wallet-relying parties are described in certificates, how those certificates relate to national registers and EU trust lists, and how they link back to the registration rules in Commission Implementing Regulation 2025/848.

These ETSI texts work together with ARF, and give concrete guidance—as opposed to high-level legal text—for technical teams, so that they are able to build specific and compliant products.

On top of that, there is a reference implementation with open-source code for:

Wallet apps for iOS and Android.

Issuer and verifier services.

Helper libraries for features such as SD-JWT and wallet mediated signing flows.

As of late 2025, they are updated frequently as new acts on topics such as wallet certification, cross-border identity matching, and incident handling come into force.

How to verify digital identities like EUDI

A European Digital Identity Wallet can only work if other parties trust the identity inside it.

First, the holder has to be linked to a real person in a reliable way. Second, each credential inside the wallet has to be verifiably authentic and unaltered when it is presented. For these purposes, EUDI follows a robust, three-part scheme, now considered standard for digital identity solutions:

An issuer that creates and signs credentials.

A holder that stores them in a digital wallet.

A verifier that checks those credentials when needed.

The issuer’s role

An issuer is any trusted party that asserts something about the holder. In a government context this could be:

A ministry or population register issuing a digital ID.

A driver's license authority issuing a mobile driver’s license.

A university issuing a diploma or enrollment credential.

Issuing not forced?

The Regulation can say which public bodies should act as issuers and can set rules for “authentic sources”, but it cannot force every possible issuer across the European Union to connect on day one. Outside the core registers and large public institutions, adoption will be voluntary. A university, employer or professional body will only start issuing wallet credentials if it sees a clear benefit, funding and a realistic integration path.

The issuer creates a credential with claims about the subject (name, date of birth, license categories, degree details) and signs it with its private key. The credential also carries data that lets others tie it back to the issuer; for example, an identifier and public keys published in a registry or metadata service.

Once signed, the credential is handed over to the holder. The issuer does not need to see where it is used later, which is a big privacy difference compared with live database lookups.

Holder’s role

The holder is the person or organization the credential refers to. They keep their credentials in a digital ID wallet, typically a secure app on a smartphone.

For the holder, this digital identity wallet is both a storage and control panel. They can:

See which credentials they have.

Decide which ones to present—and to whom.

In more advanced setups, choose to share only selected attributes—not the entire credential.

Because the wallet is tied to keys under the holder’s control, it can also prove that the person presenting a credential is the legitimate subject, not someone who just copied a file.

Verifier’s role

The verifier is any party that needs to check something about the holder: a bank opening a new account, a telecom operator checking a SIM registration, a platform checking age, a public authority granting access to a service, etc.

In this model, the verifier does not call the issuer’s database each time. Instead, it:

Requests a credential or a subset of its data from the holder’s wallet.

Checks the digital signature on that credential against the issuer’s public key.

Checks status data such as expiration and revocation.

Applies its own business rules to decide whether what it sees is enough for the action at hand.

The trust comes from cryptography and controlled registries of issuers and keys, and not from live database queries.

BONUS: IDV vendor’s role

Around this triangle, there is a fourth role that often gets left out: the initial identity verification layer.

Document and biometric verification solutions by vendors like Regula support a lot of the heavy lifting that issuers and verifiers need to do in a wallet model:

Issuing credentials into a wallet: Before a government can safely issue a credential, the user must first scan their passport or ID card in an app. The chip is read via NFC, security features are checked, the selfie is matched to the chip photo, and only then does the credential enter the digital identity wallet.

Recovering a wallet after device loss: If a user loses their phone and needs to restore their EUDI Wallet on a new device, the wallet provider can run a robust recovery flow. The flow will include rescanning an e-passport or ID card and repeating biometric checks.

Step-up checks for high-risk actions: Sometimes, a bank may accept EUDI Wallet credentials for login, but for a high-value credit line or a first large transfer, more verification is required. The bank then asks the user to scan a physical document and take a selfie in the same session, verifying the document chip and face match, then cross-checking with the wallet data.

The current state of EUDI

As of late 2025, the main legal acts are in force: the Architecture and Reference Framework has reached several stable versions. The actual implementation, however, is not proceeding as swiftly as expected, mainly due to skepticism by many involved parties.

The reasons for skepticism are plentiful: technical complexity, financing, and risks, among others. And even if official documents go into great depth on protocols and supervision, but say little about who pays to build, host and maintain wallets, or how issuers and relying parties will be charged in day-to-day use.

Legal and technical footing

Implementing acts adopted in 2024 and 2025 cover topics such as:

Protocols and interfaces for wallet interactions.

Certification and listing of wallet solutions.

Registration of wallet relying parties.

Cross-border matching of identities.

Handling of security breaches that affect European Digital Identity Wallets.

Rules for electronic attestations of attributes and qualified certificates.

The ARF documents reference these acts and translate legal terms such as “wallet solution,” “authentic source,” or “qualified attestation” into component-level requirements. The same documentation references standards bodies and profiles, so that implementers can align on a common set of building blocks.

On the code side, the EU Digital Identity Wallet reference implementation includes documentation, wallet apps, services for issuing and verifying Person Identification Data and mobile driver's licenses, and helper libraries for core flows. There is also a separate reference stack for age verification that reuses the same ideas for a narrower use case.

Integrators can deploy these components in sandboxes, connect their own test services, and learn how a standard EUDI Wallet behaves before they work with national production apps.

The age-verification mini wallet and pilots

One of the clearest real deployments is the age-verification “mini wallet” built to support the Digital Services Act. In July 2025, the European Commission published an Age Verification Blueprint with a mobile app, APIs, and a governance model for age checks on online platforms.

The Commission explicitly describes this software as a “mini wallet” based on the same architecture and reference framework and technical specifications as future European Digital Identity Wallets. It lets a person prove they are above a chosen age threshold, initially 18, without sharing their name, address, or full date of birth. The code and documentation are published openly so that Member States can connect the app to their national identity sources.

Five Member States (Denmark, Greece, Spain, France and Italy) are piloting this model. Platforms receive a compact “over 18” or similar token instead of raw identity data. For the EUDI program, this is a live test of attribute-only proofs, mobile user experience, and wallet-platform interaction under DSA enforcement.

In parallel, the large-scale pilots under the Digital Europe Programme (POTENTIAL, NOBID, DC4EU, EWC, and the newer APTITUDE and WE BUILD) are exercising a wide set of scenarios: government logins, SIM registration, education credentials, social-security documents, travel flows, payments and signatures. Some flows use synthetic data for the most sensitive actions; others use real people in clearly defined cohorts. NOBID’s signing work, for example, used test data because no wallet had yet been notified under eIDAS, but the flows mirror real onboarding and signing processes.

EUDI-related national ID projects

Several EU states already had very mature digital ID systems before EUDI came along, and those systems are now being extended or coupled to wallet projects. Let’s take a look at some of the most advanced ones.

Denmark: MitID

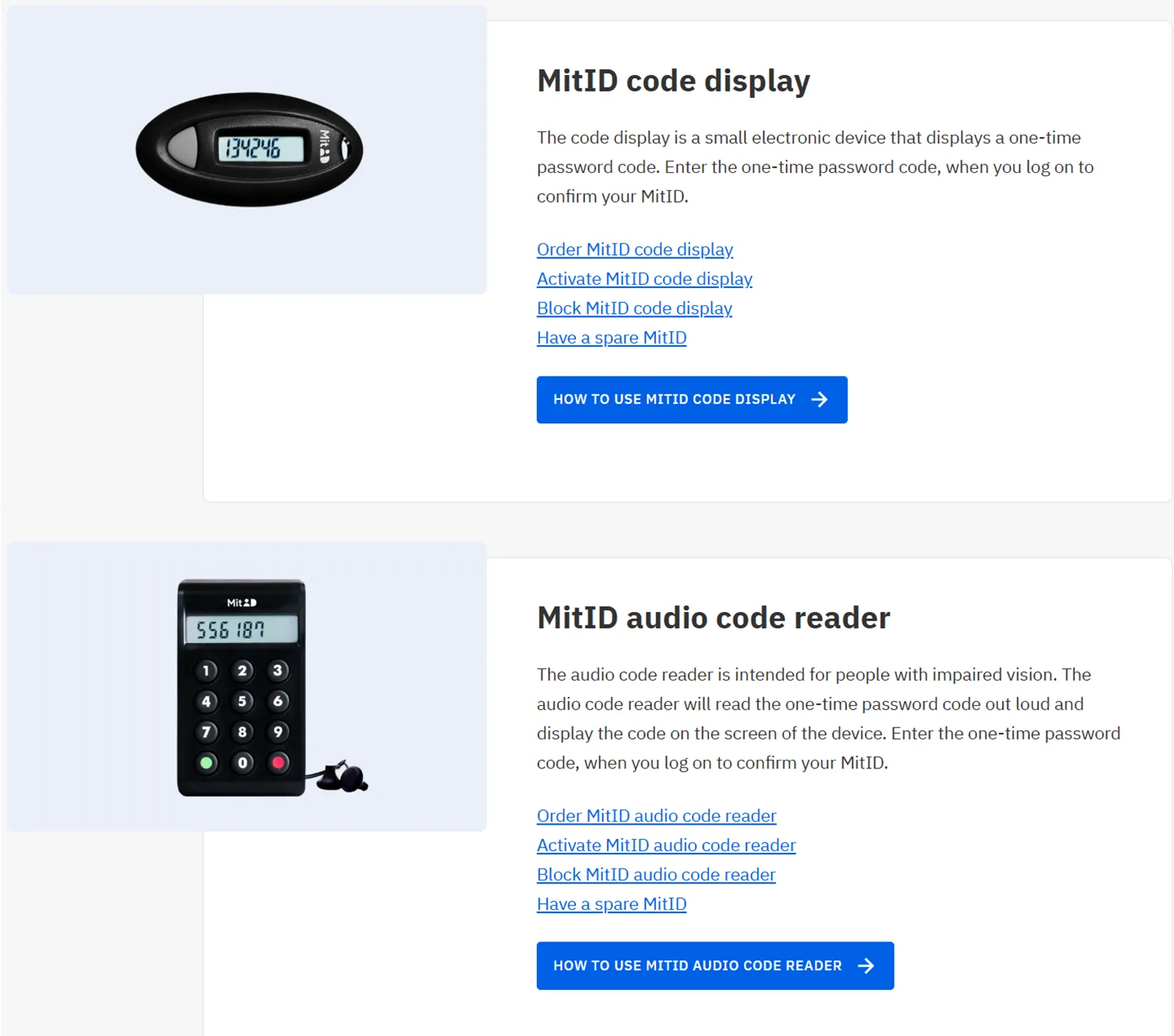

Denmark already has one of the most entrenched digital ID schemes in the European Union. MitID is the personal digital ID used for online banking, the main government portal, tax, health services, and many other public and private interactions.

Interestingly, the app can be supplemented by a number of simple yet robust hardware devices, meant for various target groups.

MitID is not yet certified as an EUDI Wallet, but in practical terms it already behaves like a national identity wallet front end. Denmark is also part of the age-verification mini wallet project, which gives it additional experience with wallet-style age proofs and regulated platforms.

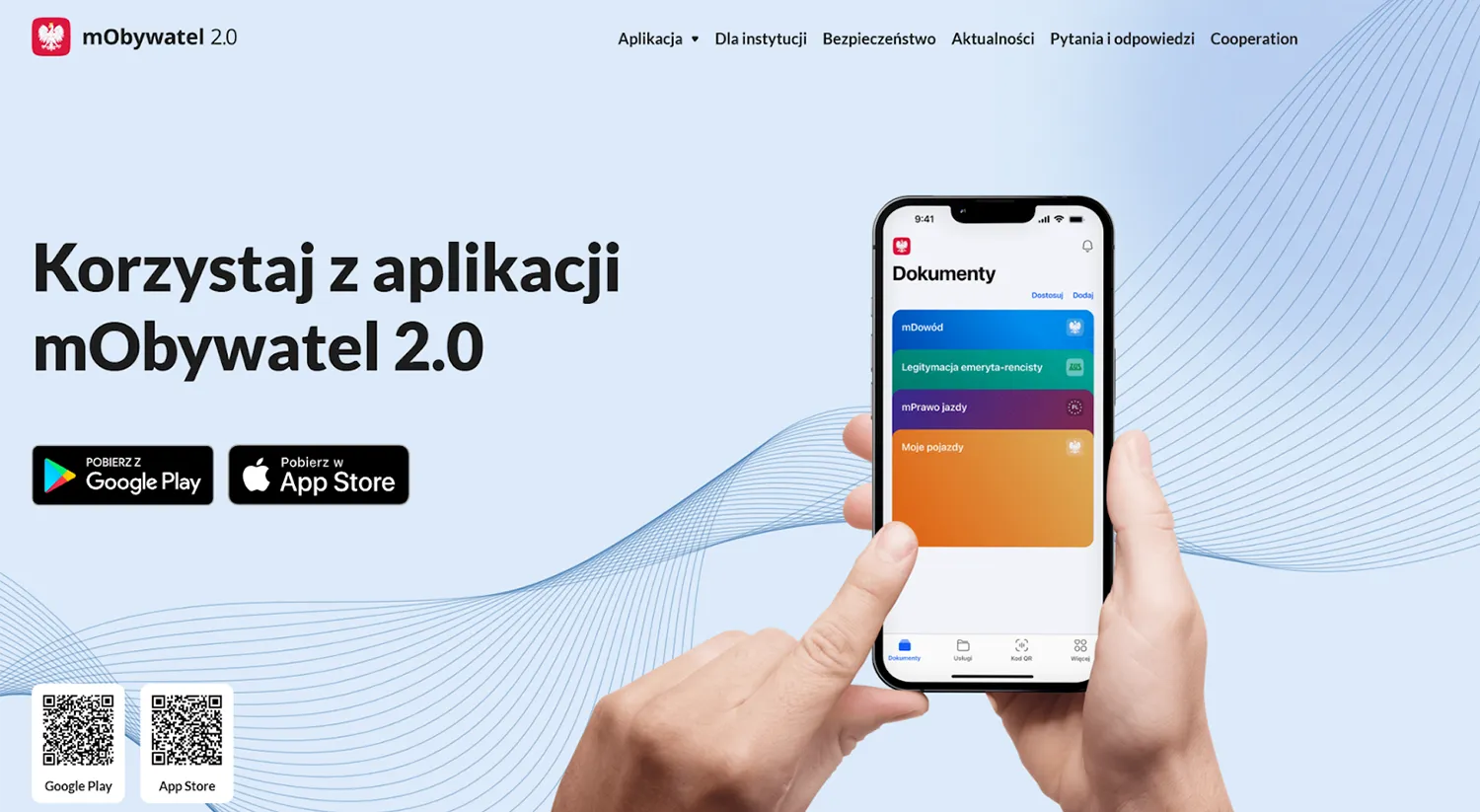

Poland: mObywatel

Poland’s mObywatel is another strong example of a national wallet moving toward EUDI status. The app holds a digital ID document called mDowód, which includes driver's licenses, vehicle data, and various certificates, and it is widely used for interactions with authorities and some private services.

Polish press and specialist outlets report that mObywatel 3.0 is planned for November 2026, and that the update is driven by the need to align with eIDAS 2 and the European Digital Identity Wallet concept. It is expected to add cross-border use inside the EU and free qualified signatures, while keeping the app familiar for existing users.

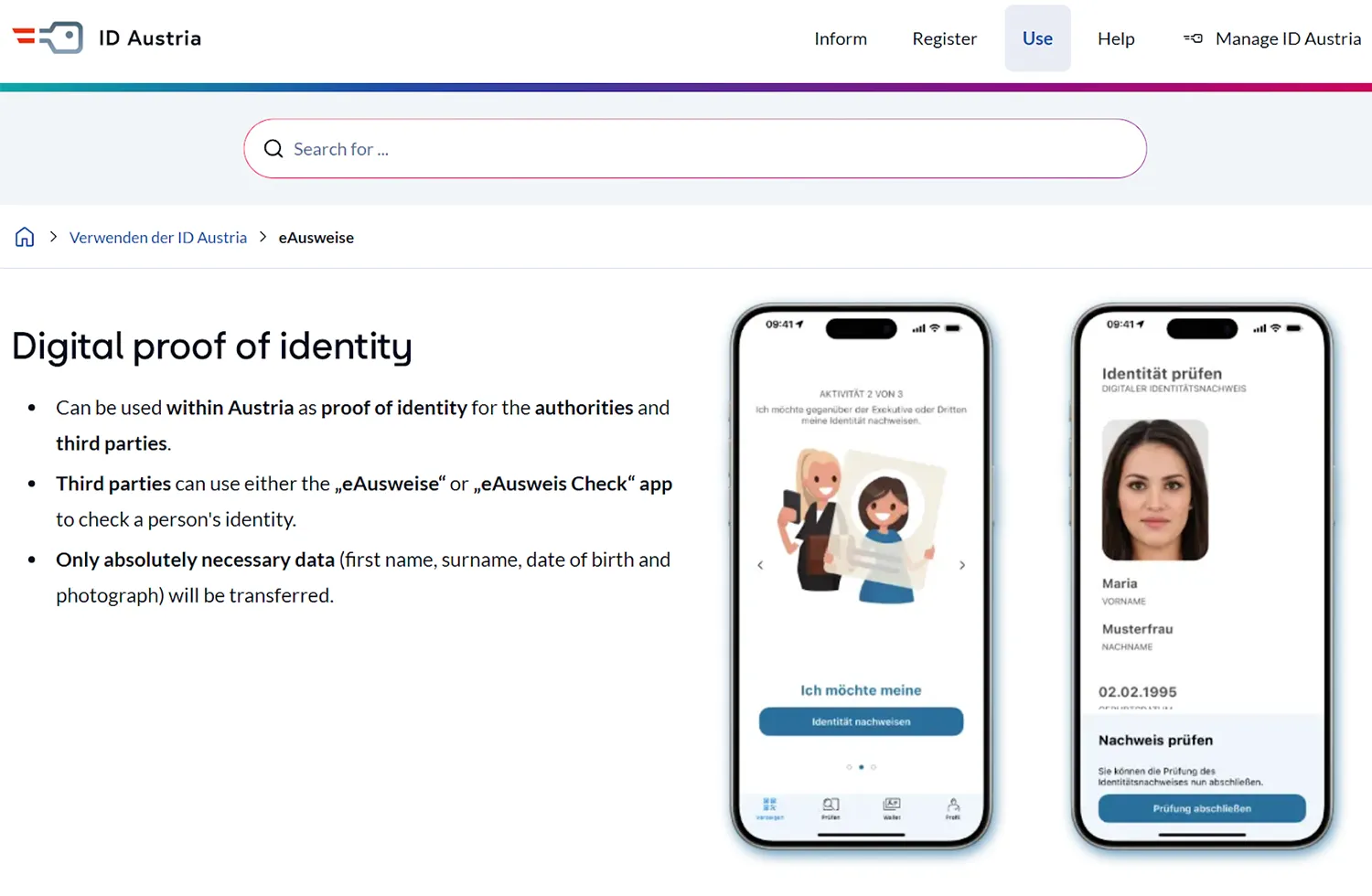

Austria: ID Austria and eAusweise

Austria’s ID Austria app provides high-assurance digital identification for roughly two hundred online services, both public and private. Citizens can use it for tax, business registers, official communication, and qualified signatures.

In parallel, the eAusweise allows people to present a digital driver's license and age proofs on their phones, which closely matches the type of mDL-style credential that an EUDI Wallet is expected to handle.

Belgium: itsme and MyGov.be

Belgium uses a public-private mix. The itsme app, operated by a consortium of banks and telecom operators, is a widely used digital ID that works for both government portals and commercial sites. It lets users log in, share identity data, and sign documents, and has around seven million users and more than a thousand relying parties.

On top of that, the federal government has launched MyGov.be, which acts as a portal and digital identity wallet for official documents and messages. Citizens can store certificates, access personal data, and read official messages in one app. MyGov.be can be activated using an eID card or an itsme account.

The future plans for EUDI

For now, digital IDs are only relevant to Europe, not the whole world. Achieving a globally accepted, fully digital ID system in the near future involves significant challenges, including the need for extensive cooperation and trust between nations. But not every country even has electronic identity documents yet.

As we move towards a future where digital identity is the norm, and users increasingly demand mobile identification, this evolution cannot be stopped or slowed down. Digitalization of identity documents is a logical step. Still, it requires much careful preparation.

From late 2025 onwards, the development of EUDI revolves mainly around certification and scale.

On certification, the revised eIDAS rules and the EU Digital Identity Wallet Regulation state that each Member State is expected to notify at least one EUDI Wallet that passes a conformity assessment. Implementing Regulation 2025/849 sets up the EU list of certified EU Digital Identity Wallets, while other acts describe how wallet solutions are evaluated, how relying parties are registered and supervised, how cross-border matching works, and how incidents must be reported.

For national teams, this means digital identity wallet projects must line up with the Architecture and Reference Framework and satisfy its requirements. For relying parties, especially in banking and telecoms, this involves registration and compliance duties once they claim to accept an EUDI Wallet for high-assurance login.

The incentive question

Interestingly, what the regulation does not spell out in detail are the incentives: if wallets are free for holders and also free for issuers and verifiers, then the cost of development, hosting, certification, and audits falls almost entirely on public budgets. If, instead, part of that cost is recovered from service providers or issuers, many smaller organizations may hesitate to add wallet flows when they already have efficient processes in place.

On scale, the pilots have already shown that the basic patterns work for education, social security, travel, signatures, SIM registration, and bank accounts. Over the next two years, the focus will shift to moving these flows into production and dealing with real error rates, support tickets, and fraud attempts. POTENTIAL, NOBID, DC4EU, EWC, APTITUDE, and WE BUILD will keep feeding practical lessons back into the toolbox, especially around interoperability and user experience.

How Regula's solutions complement the EUDI Wallet

European Digital Identity Wallets are facing strong headwinds. Most EU residents will see the wallet as a digital version of their ID, so they are unlikely to accept paying a per-use fee to a private provider each time they identify themselves. And if wallets are offered “for free” at the point of use, the cost has to surface elsewhere: in public budgets, in contracts with wallet vendors, or in fees paid by banks, telecoms and other relying parties.

Even if the EUDI Wallet manages to bring real change to identity verification, one thing will not change: the need for solid proofing at the issuing level. Before any wallet can hold trusted credentials, someone has to check that the person, the document, and the register data all match—and that is where Regula’s technology comes in.

Complete identity verification procedures can be carried out by solutions like Regula Document Reader SDK and Regula Face SDK, which can easily integrate with your existing mobile or web applications.

For EUDI Wallets, Regula Document Reader SDK can validate ePassports and eIDs at onboarding and recovery, re-check chip data on the server, and pass structured, verified attributes into wallet issuance flows.

Regula Face SDK then ties those attributes to a real person through strong biometric checks, so issuers and relying parties can be confident that the wallet holder, the document, and the register record all refer to the same individual even in fully remote scenarios.

Have any questions? Don’t hesitate to contact us, and we will tell you more about what our solutions have to offer.