As estimated by the UN, around $2 trillion is laundered worldwide annually, which is equivalent to a staggering 2% of global GDP. There are many methods that criminals use to make their illicit funds “clean,” but there are few as simple in execution and hard in detection as smurfing (not to be confused with the same term in gaming).

In this article, we will explore the mechanics of smurfing, its implications, and the anti-money laundering (AML) strategies to combat it.

Get posts like this in your inbox with the bi-weekly Regula Blog Digest!

What is smurfing?

Smurfing is a deceptive financial technique where large sums of illicit money are broken into many smaller transactions to evade detection by regulators. It exploits the fact that banks in many jurisdictions only flag cash movements of over $10,000, and makes sure no single transaction goes over that threshold.

Smurfing vs. structuring

It’s easy to confuse smurfing with basic structuring, since both are centered around breaking down transactions; but the main difference lies in scale and personnel. While smurfing is done by a network of accomplices, structuring involves a single individual splitting one big amount into smaller deposits or withdrawals. But just like smurfing, structuring is illegal: even if the money is legitimately earned, the intentional evasion of reporting is a crime in many countries.

Smurfing typically occurs during the placement stage of money laundering, the initial step where dirty money is introduced into the financial system. Drug trafficking, illegal gambling, and corruption are the most common sources of such money—and none of them can be openly deposited without arousing suspicion.

.svg)

In a typical scheme, each smurf may simply deposit an amount just under the limit that requires a report (for example, $9,900). If they are willing to further fragment the activity, they may visit different bank branches or ATMs, or use a mix of financial instruments like money orders and prepaid cards.

Once the placement is done, the funds move into the layering stage. Each smurf’s account may wire its balance to a central account abroad, or purchase monetary instruments and then consolidate them. This way, they create a dense web of transactions that makes it very labor-intensive for investigators to trace the fund’s origins; by the time the web is untangled, the money will have already been withdrawn.

The three red flags of smurfing in banking

Smurfing in banking may be hard to spot, but it is, ultimately, still a pattern one can trace. That’s why vigilant institutions can often spot the clues if they know what to look for:

Multiple low-value deposits that aggregate to a large amount: For example, there may be dozens of cash deposits just under the $10,000 threshold within a short period. A classic sign is a customer making frequent deposits at $9,500 or similar “round numbers” just below the report limit. The bank’s systems may notice that, over a week or a month, the total amount far exceeds $10,000, even though no single deposit did.

The same person or group using many locations or accounts: Smurfing often means deposits at different bank branches or ATMs on the same day to avoid attention. If a bank sees one client’s accounts receiving cash at three branches across town in one afternoon, or a set of new customers all depositing in one branch, then quickly wiring money out, it should raise suspicion.

Transactions inconsistent with the customer’s profile: If an account that was low-activity suddenly starts receiving numerous small deposits or transfers, it could also indicate smurfing. Common examples include a modest salary account that has daily cash deposits from unknown sources, or a small shop that operates with amounts far beyond its normal revenue.

A word on cuckoo smurfing

Cuckoo smurfing is a term used primarily within the Australian context; however, it is slowly seeing more widespread use. It is considered a more sophisticated scheme, where criminal money is laundered through the bank account of an innocent person expecting a transfer. In a simplified way, cuckoo smurfing can be summed up as this:

An individual wants to send money to a family member or business in another country.

The individual goes to a remittance agent and deposits their funds, believing it will be sent to the intended recipient. Unbeknownst to them, the remittance agent is corrupt and is part of a money laundering network.

The agent intercepts the transaction instructions and instead arranges for an equivalent amount of dirty money already in the destination country to be deposited into the recipient’s account.

From the recipient’s perspective, they simply received the expected payment, and they have no idea it came from criminals’ domestic stash. Meanwhile, the original funds the sender deposited are secretly diverted to the criminals, completing the swap.

The funds used for cuckoo smurfing most commonly come from the Middle East and Southeast Asia, where alternative remittance is still one of the main methods of transferring money to individuals in Australia.

Preventing smurfing: AML best practices

Know Your Customer (KYC) and Customer Due Diligence (CDD)

Strong KYC procedures at onboarding and ongoing due diligence can massively deter smurfing, as they make it harder for criminals to open the multiple accounts needed for these schemes. With KYC/CDD, banks verify each customer’s identity and assess their risk profile, so that if a low-risk customer suddenly begins acting like a high-volume cash courier, the bank can detect the anomaly quickly.

CDD also involves gathering information on the source of funds and the purpose of accounts. If a person claims to be a modest salaried worker but is depositing large cash sums, that discrepancy will prompt further scrutiny. There is also enhanced due diligence, which can be applied to higher-risk customers (e.g., those with political exposure, or from high-risk countries), meaning their accounts are monitored even more closely.

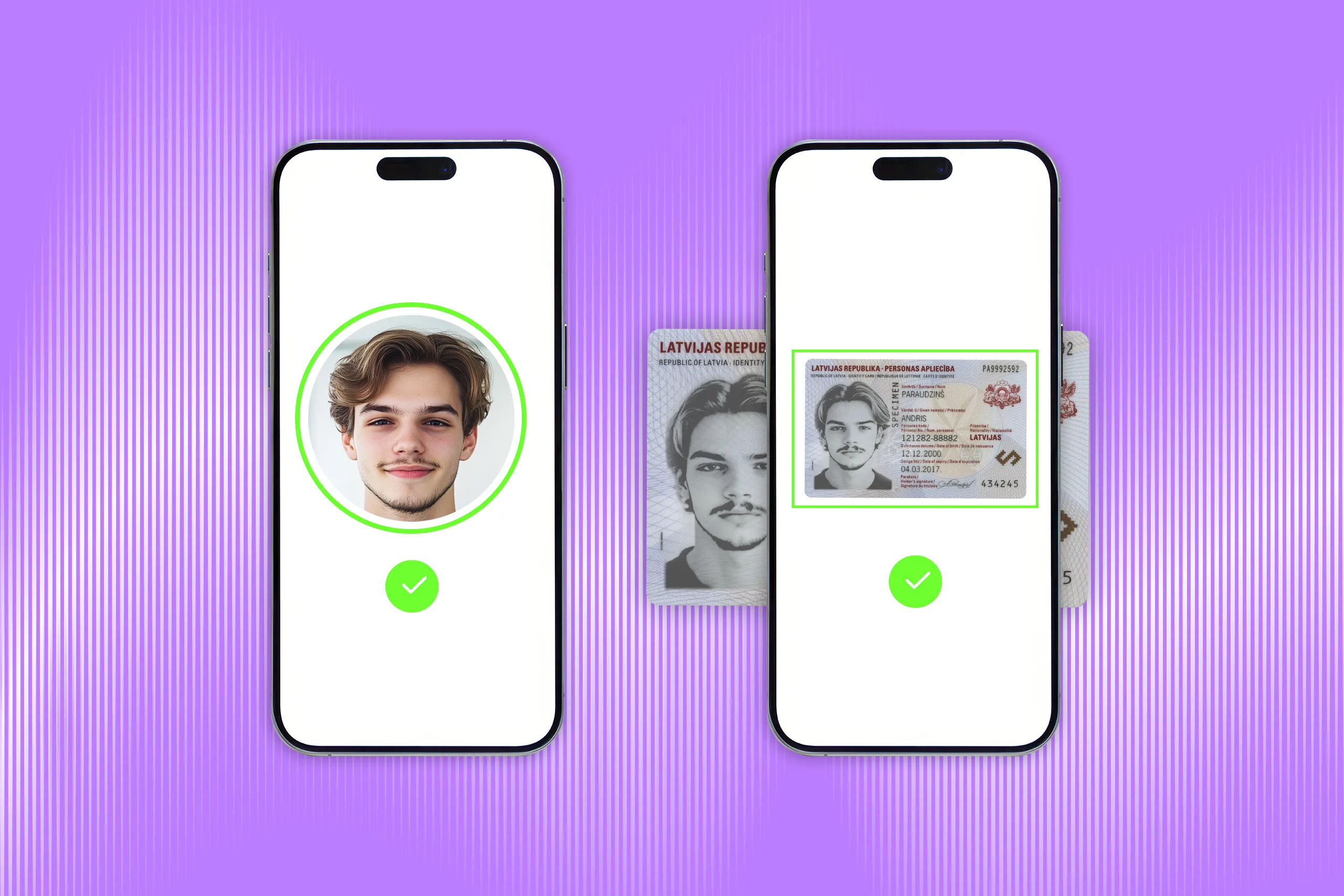

Solutions like Regula Document Reader SDK and Regula Face SDK are widely used in this context: they not only provide the means to verify one’s ID and facial biometrics upon registration, but also re-verify the account owner in case of suspicious activity.

Transaction monitoring

Banks also employ AML software that tracks all transactions and uses rules or algorithms to flag suspicious behavior. The system can be configured to raise an alert if more than $X in cash is deposited by the same customer in a rolling 7-day period, or if multiple new accounts receive deposits from the same paymaster.

Additionally, modern systems increasingly use machine learning to identify complex patterns that rule-based systems could miss. They can link entities by shared attributes (e.g., device IDs, IP addresses, or login patterns) to uncover a web of smurfs working together.

Staff training and collaboration

Front-line staff at banks, such as tellers and branch managers, are often the first to observe structuring behaviors, which makes staff training vital. Good training ensures that employees know the red flags of smurfing and can internally report suspicious activity to the compliance unit.

Cross-institutional teamwork is just as important: banking groups are known to centralize their AML monitoring so that a customer can’t smurf by using different branches without notice. Moreover, banks can share intelligence through financial intelligence units: if a bank files a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) about a smurfing scheme, other banks can be notified to look for related activity in their institution.

Regulatory responses to smurfing

From a legal standpoint, both smurfing and structuring are serious financial crimes. Even if the funds come from a legitimate source, intentionally dodging reporting rules is forbidden in many countries worldwide, including the United States, Canada, the UK, Australia, and most of Europe.

The American example

Under the US Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), a person convicted of structuring can face up to 5 years in federal prison and fines up to $250,000 for individuals. If the structuring is part of broader criminal activity or exceeds $100,000 over a year, penalties can double to 10 years imprisonment and higher fines.

In the case of organized, large-scale smurfing, penalties can be even more severe. Money laundering (of which smurfing is a method) in the US can lead to up to 20 years in prison per count and millions of dollars in fines.

Global regulators have also put measures in place to combat smurfing in banking. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommends that institutions have the aforementioned cash thresholds in place and monitor any structuring attempts. As a result, many jurisdictions have converged on similar rules: for example, Canada, the EU, and Australia also mandate reports for large cash transactions around $10,000, and suspicious transaction reporting for any amount that looks structured or unusual.

Nowadays, banks are expected to have compliance programs capable of detecting and preventing smurfing (e.g., trained staff or automated monitoring). Failure to do so can result in penalties against the institution: in recent years, major banks have been fined for not adequately monitoring accounts that engaged in obvious structuring.

Regula’s role in smurfing prevention as ID verification experts

Smurfing in AML often relies on fake or stolen identities to open numerous accounts. Cutting off that capability at the onboarding stage makes it much harder to pull off. That’s why more and more institutions are employing advanced ID verification solutions so they know that their customers are who they claim to be, and aren't duplicating identities.

Identity verification procedures can be carried out by solutions like Regula Document Reader SDK and Regula Face SDK, which can easily integrate with your existing mobile or web applications.

Regula Document Reader SDK processes images of documents and verifies their real presence (liveness). The software automatically identifies the document type, extracts all the necessary information, cross-validates it, and confirms whether the document is genuine with a comprehensive set of authenticity checks. Regula Document Reader SDK supports all major dynamic security features, including holograms, optically variable inks (OVIs), multiple laser images (MLIs), and, most recently, Dynaprint®.

At the same time, Regula Face SDK conducts instant facial recognition and prevents fraudulent presentation attacks such as the use of static face images, printed photos, video replays, video injections, or masks. The solution can perform both 1:1 face matching (matching the user’s live facial image to their ID) and 1:N face recognition (comparing the user’s facial data against a whole database).

In practical terms, Regula’s software can be integrated as the key part of your KYC/CDD process. Eager to learn more? Book a call, and we will help you make your identity verification compliant, secure, and customer-centric.