Businesses and governments increasingly engage with individuals who are not native residents.

According to the UN’s World Migration Report 2024, the global number of migrants has grown from 150 million in 2000 to 281 million in 2024. Of those, 169 million are migrant workers, and 35.4 million are refugees.

No matter the reason for being abroad—whether working, studying, or traveling—non-residents must often prove their identities. This can be tricky for organizations, as these individuals carry a wide range of identity documents.

This blog post explores common identity verification (IDV) scenarios involving non-residents, outlines key challenges, and offers best practices to handle them effectively.

💡Curious about other ID documents and what makes them unique?

Read our expert reviews of:

Common identity verification scenarios for foreign nationals

Let’s start by clarifying who non-residents are in the IDV context. This helps define which organizations they interact with, both before and during their stay, and for however long they remain in the country.

💡The starting point in a non-resident’s journey is often a visa center or border control checkpoint. But some travelers bypass these stages—for example, in regions with open-border agreements.

Generally, non-residents fall into at least six categories:

Regular traveler

This group includes short-term visitors—tourists and business travelers. Typically, they cross borders using standard travel documents, mainly passports that may feature visas.

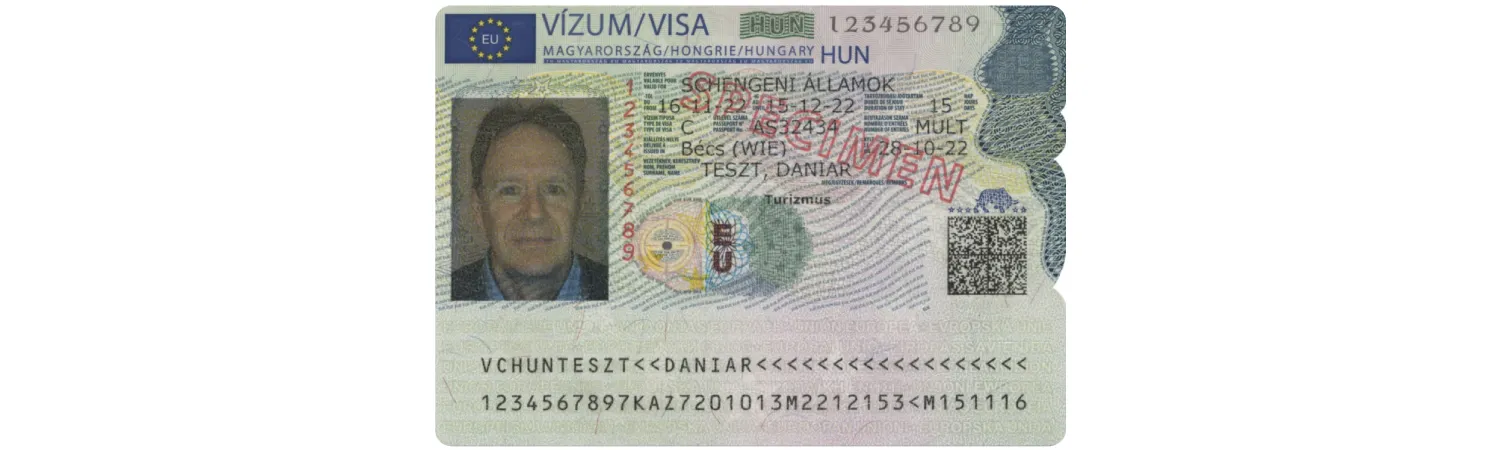

Importantly, the length of stay depends on the visa type and/or the traveler’s country of residence. EU countries typically issue type C visas for tourists, allowing stays of 90 days within any 180-day period, with validity periods ranging from a few days to one or two years. Canada grants long-term visitor visas that can be valid for up to 10 years. Some countries also have visa-free entry agreements with defined stay periods—commonly from 30 days to one year.

Visas issued under bilateral recognition agreements—like those between Schengen countries—typically share a common design. A type C visa, as shown in this Hungarian example, indicates tourism as the primary purpose of visit.

Most short-term visitors interact with businesses in travel and hospitality. Others may use in-person services such as telecom or rentals during their stay.

What other travel documents exist besides passports?

Citizens of some countries can use domestic IDs—national ID cards or residence permits—for trips to neighboring states or territories under reciprocity agreements. Examples include member countries of the European Union, MERCOSUR, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Citizens of countries with overseas territories often have similar privileges.

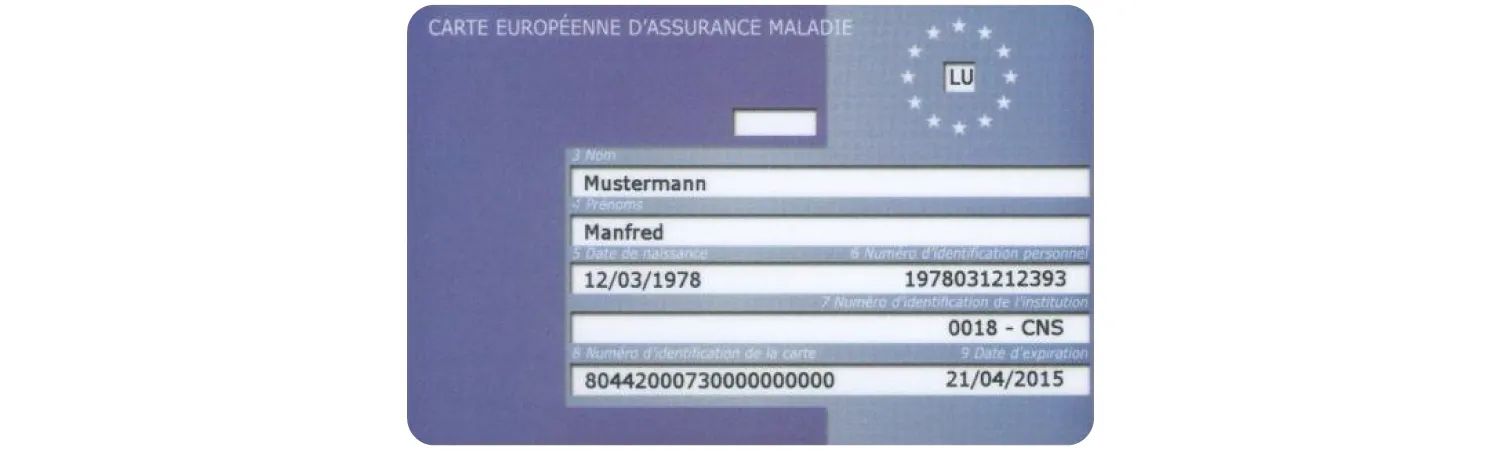

Some exceptions are even more specific. For example, travelers from Denmark to Greenland can use their healthcare insurance cards for boarding.

Residents of Argentina—a MERCOSUR member—can use their national ID cards for cross-border travel to other member countries.

International student

Unlike regular travelers, students stay abroad for an extended period, at least for the duration of their studies. In many countries, they need a specific student visa to enter. In addition, most states issue residence permits that cover the full study period.

Student visas are issued under specific types. In China, the student visa type is X1.

If a student comes from a country with a reciprocal agreement—say, from Germany to the Netherlands—they may only need to register with a school or university and obtain local health insurance. This means they also interact with government agencies early in their stay.

The European Health Insurance Card provides access to medically necessary, state-provided healthcare during temporary stays in any of the 27 EU member states, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, or the UK. The cards follow a similar layout and dataset—like this example from Luxembourg.

During the residency, international students typically engage with healthcare providers, telecom companies, landlords, and various digital services—from food delivery apps to mobility services. They may also be eligible to use their driver’s licenses abroad. But this also works for regular travelers.

International Driving Permit (IDP)

Sometimes, non-residents need an IDP to legally drive in a foreign country. This booklet-like document contains an official translation of a person’s national driver’s license and is issued through a global network of AIT/FIA* organizations.

Whether or not an IDP is required depends on bilateral agreements between the country of origin and the host country. Since these agreements can change frequently, requirements may vary over time. Importantly, an IDP does not replace a valid domestic driver’s license!

*AIT – Alliance Internationale de Tourisme (International Touring Alliance); FIA – Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (International Automobile Federation)

Get posts like this in your inbox with the bi-weekly Regula Blog Digest!

Expatriate

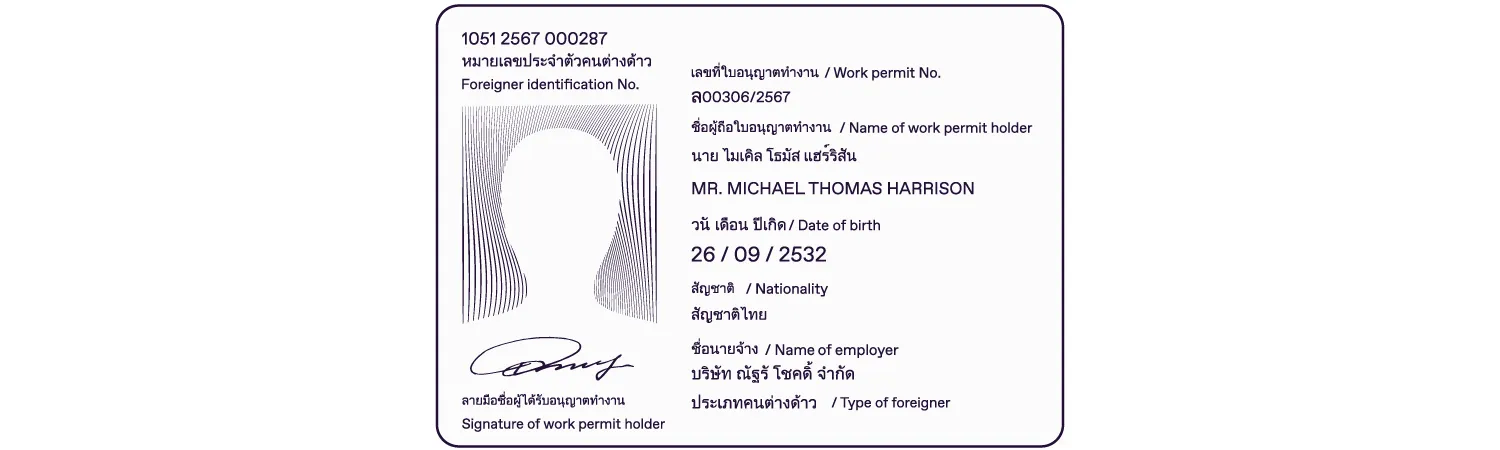

The expatriate journey is similar to that of international students. The key difference lies in the documents required for legal entry. Most countries require a work visa and/or a work permit for non-resident employees.

International workers in Thailand are required to obtain a work permit—a passport-like booklet containing personal details in Thai and a photo. It also includes an identification number that links the holder to the local identification system.

In the US, some international workers must apply for an employment authorization document (EAD).

In the US, an EAD can be issued to temporary residents. International students who want to work during their studies are one example.

In addition to getting a residence address and health insurance, expatriates often need to open a bank account. For verification, a passport with a valid visa is usually required.

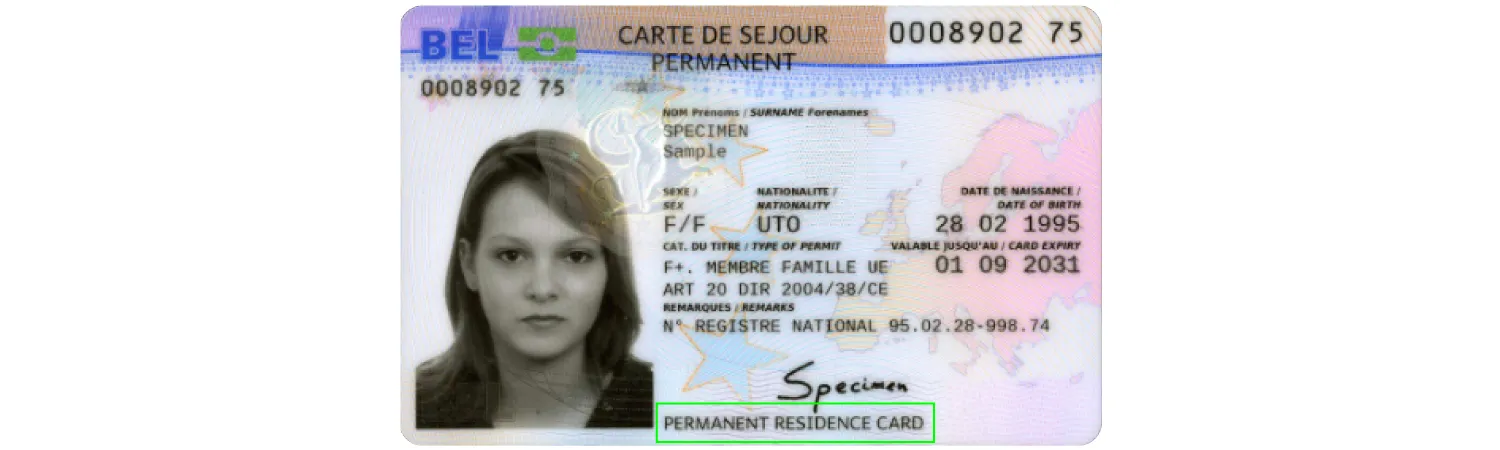

Expatriates coming for long-term, contract-based work may apply for a residence permit once their work visa expires. There are two main types—temporary and permanent—which differ in their validity. However, each country typically offers its own additional options. For instance, Belgium has at least ten types of residence documents for non-citizens.

In Belgium, a permanent residence card in the F+ category is issued to family members of EU citizens or Belgians who come from third countries.

A specific example of an ID for expatriates is Mexico’s consular identification card (Matrícula Consular). Issued by Mexican consulates, this card serves as an official ID for Mexican citizens living abroad, primarily in the US. It includes the holder’s photo, ID number, and address, and is accepted for various purposes such as tax payments and banking.

Issued by Mexican authorities, the consular identification card is valid for identification purposes abroad only.

Digital nomad

Travel workers are a subcategory of skilled expatriates who stay in a country for shorter periods, ranging from a few months to a few years. Digital nomads emerged as a distinct group in the late 2010s, gaining momentum after the pandemic.

The rise of government-backed programs aimed at attracting senior-level professionals in knowledge-based industries has fueled this trend. Eligible individuals can often apply for digital nomad visas remotely.

Once in the country, digital nomads typically interact with businesses in retail, banking, insurance, and telecom. In most cases, their main proof of identity is a valid passport or identity card, which serves for verification purposes across these services.

Diplomat

Individuals arriving in a country with a diplomatic mission follow a unique path. In practice, it’s a mix between a business trip and expatriation. But unlike regular travelers or contract workers, diplomats, high-ranking officials, and often their family members hold special passports, which typically grant visa-free entry and a degree of immunity from border inspections and local laws.

Diplomatic passports are ICAO-compliant and similar in layout to standard passports but have a distinct cover color. Some also include the holder’s status—often shown near the expiration date.

The Slovak diplomatic passport (left) is an exception, as it shares the same cover color—burgundy—as the country’s regular passport (right). Both versions were updated in 2024 and look very similar, differing only in the inscription on the cover and above the main portrait and the passport code in the MRZ.

The UAE diplomatic passport includes the holder’s designation alongside standard personal information. The tricky part is that the designation, as well as some other details, is written in Arabic.

Diplomatic passports, such as the UN Laissez-Passer or Malta’s Order service passport, are examples of internationally recognized travel documents for diplomats.

Despite their special status, diplomats are still considered regular residents in a host country. Many hold both diplomatic and ordinary passports. For example, British diplomats may use their standard passport for personal travel and their diplomatic passport for entering or exiting the country where they are posted on official duties.

For this reason, diplomatic documents are typically handled only by border control officers or airlines. Businesses can verify these individuals using regular IDs.

Refugee

This category includes individuals seeking asylum abroad. While many initially enter a country using their own travel documents—usually passports—they often require new identity documents later, as returning to their country of origin may not be possible.

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), at least 79 countries issue machine-readable convention travel documents (MRCTDs), including 26 that provide electronic versions. These documents are accepted by 81 countries. As the UNHCR notes, MRCTDs should also be recognized as valid IDs by banks and other institutions, helping refugees access services and send remittances to family and friends. In practice, refugees use many of the services other residents use, including telecom and ecommerce.

MRCTDs are ICAO-compliant and resemble standard passports issued by the country of asylum. They typically have a blue cover and a specific inscription.

A convention travel document issued by Lithuania.

Beyond UN-issued refugee travel documents, many countries provide IDs for non-resident internationals and stateless individuals. Examples include alien passports, travel documents for foreigners, and certificates of identity. The key differences between them lie in their validity periods and eligibility requirements.

For example, a Swedish alien passport can be granted to a non-resident with a residence permit in three cases: they are under protection and cannot travel to their country of origin to obtain a passport; they are a citizen of a country whose passport is not accepted in Sweden; or they are unable to obtain a passport from the authorities in their country of origin. This document can be used for travel to most countries.

An alien passport issued by Sweden is biometric and valid for up to three years.

The reasons for applying for a Polish travel document for a foreigner are similar. It is issued to individuals who have no valid passport and cannot reasonably obtain one from their country of origin. The document allows for multiple border crossings.

.webp)

A Polish travel document for foreigners is valid for one year only.

New Zealand also issues special travel documents to refugees. For example, certificates of identity are given to individuals who are not citizens of New Zealand and cannot obtain a passport from their country of citizenship. To qualify, they must be physically present in New Zealand. This document can be valid for up to two years.

A certificate of identity issued by New Zealand is a biometric document valid for two years.

Major verification challenges with foreign resident IDs (and how to solve them)

While many organizations are familiar with verifying identity documents like passports and visas for regular travelers and digital nomads, handling IDs from other non-resident groups often poses additional challenges. These issues can slow down onboarding and, worse, allow identity fraud to slip through unnoticed.

Here are the main challenges that companies in banking, telecom, hospitality, and government sectors may face:

Lack of standardization

There are countless ID documents worldwide, each with its own format, language, and security features. Unlike machine-readable passports standardized under ICAO’s Doc 9303, domestic IDs often vary greatly and can appear unfamiliar to organizations in other countries.

This lack of standardization slows down identity verification and increases the risk of errors—especially when ID data is extracted or transcribed manually. A Regula global survey found that 41% of businesses cited the absence of unified document standards as a major challenge when verifying international customers.

Universities enrolling foreign students, financial institutions conducting customer due diligence, and government agencies processing documents from travelers, digital nomads, or asylum seekers all face this complexity.

How to address the challenge:

A comprehensive document template database is key. And by “comprehensive,” we mean specimens numbering in the 5-figure range at least. For example, Regula’s database includes over 16,000 items from 254 countries and territories—and it’s updated regularly.

Language and script barriers

With global IDs come global languages. Verifying names, addresses, and other details is difficult when staff or basic Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software can’t read the script.

About 36% of surveyed businesses reported language differences as one of the top three challenges in verifying international IDs. The issue is especially critical for governments, healthcare and insurance providers, where any data error can have serious consequences. However, misreading ID data can impact any organization serving non-residents.

How to address the challenge:

Advanced OCR engines are essential. They must support a wide range of languages, including non-Latin scripts like Arabic or Chinese. The solution should also be able to read biometric data stored in electronic chips and other machine-readable elements such as barcodes and machine-readable zones.

Localization also matters. Non-resident customers expect ID checks in their native language. In fact, 71% of digital nomads surveyed by Regula reported having language-related difficulties during IDV.

To meet this need, Regula supports over 30 languages across its document and biometric verification solutions, with full customization for seamless user experience.

Document authenticity and fraud risks

The risk of forged or counterfeit IDs increases when verifying unfamiliar documents. Companies serving international customers are frequent targets for fraudsters, especially in sectors like car rentals or hospitality, where ID checks are often quick and manual. Without strong knowledge of security features like holograms, Optically Variable Ink (OVI) elements, security threads, or microprinting, a busy receptionist or front-desk agent may fail to spot a fake passport they’ve never seen before.

Fraudsters also take advantage of weaknesses in remote verification. AI-generated IDs, presentation attacks, and data injections are now common methods used in online scams.

How to address the challenge:

On-site ID authentication can be supported with document readers, but online IDV must rely on robust document and biometric verification software. The system should perform a full set of authenticity checks, including analysis of the visual inspection zone and machine-readable zone.

A document liveness check, which confirms the presence and authenticity of dynamic security features, is now essential due to the rise of deepfakes.

Equally important is selfie verification. The user takes a real-time photo, which is then matched with their ID portrait. Liveness detection at this step ensures it’s a legitimate person, not a printout, mannequin, or other fake used by fraudsters.

NFC verification for remote document authentication

When verifying domestic IDs, local companies often rely on data-driven checks, matching information from the document, such as name, address, and Social Security number, against government databases or watchlists. This adds an extra layer of security to the process.

However, this approach typically doesn’t work with non-resident IDs. Legal and privacy restrictions often prevent access to the issuing country’s databases. In some countries like Chile, even local businesses lack such access.

That’s where biometric documents with electronic chips offer a strong alternative. NFC-based verification allows organizations to securely extract and authenticate the data stored in those chips.

Key takeaways

Migration growth brings more international customers, even for businesses outside tourism.

Non-resident customers vary widely in background, needs, and entry points into a host country.

Businesses must verify a broad range of identity documents—from standard passports to less common certificates.

The risk of identity fraud is higher with non-residents, as both human inspectors and IDV systems may not know what genuine IDs should look like.

Effective IDV solutions must include advanced document authentication, NFC verification, and biometric and liveness checks, especially for remote verification. They also must be fully automated to speed up the process, making it error-resistant and independent of user input. Localization also helps make the session simpler and understandable for non-native speakers.